Does Uganda have an EMS? A study discusses the ambulance equipment and trained professionals lack

On July 9, 2020, Makerere University, School of Public Health carried out a specific survey on the state of EMS and acute health facility care in Uganda. They found out that at the sub-national level, there mainly was a lack of ambulance equipment, like ambulance stretchers, spinal boards, and also a lack of trained professionals.

Only 16 (30.8%) of the 52 pre-hospital providers assessed had standard emergency vehicles with required ambulance equipment, medicines, and personnel to respond to an emergency scenario properly. This is what the Makerere University understood after its survey throughout Uganda. This means that almost 70% of ambulances in Uganda do not have the capacity for medical care in pre-hospital settings.

In the background of the survey, they reported that the Ministry of Health (MoH) recognized the need to improve the ambulance services. This study has the aim to establish the status of emergency medical services (EMS) and acute health facility care in Uganda. They conducted the following assessment both at the national and sub-national levels, considering the EMS capacity at the pre-hospital and facility levels using the World Health Organization (WHO) Emergency Care Systems Assessment (ECSSA) tool.

While a few studies have been done to assess pre-hospital care in Kampala [7,8,9], no study seems to have been done to assess the status of EMS and acute health facility care in Uganda at a national level.

The aim of the study and the basics: the role of professionals and of ambulance equipment in Uganda EMS

As an emergency medical service (EMS) system, also the ambulance services in Uganda should organize all aspects of care provided to patients in the pre-hospital or out-of-hospital settings [1]. Paramedics and EMTs (also in the role of ambulance drivers), have to manage patients with specific ambulance equipment. The aim should be the improvement of outcomes in patients with critical conditions, like obstetric, medical emergencies, severe injuries, and other serious time-sensitive illnesses.

Pre-hospital care is not a field exclusively limited to the health sector, while it may involve other sectors such as police and fire department. In addition to pre-hospital care, patient outcomes are greatly impacted by the acute care delivered at the receiving health facility [4]. Patient survival and recovery are dependent on the presence of appropriately trained medical personnel, and the availability of the necessary ambulance equipment, like stretchers, spinal boards, oxygen system and so on, medicines, and supplies in the minutes and hours following the arrival of a critically ill patient at a healthcare facility [5].

EMS in Uganda: ambulance equipment and trained professionals lack – Sample size and sampling methodology

The Uganda healthcare system is organised into three main levels:

- national referral hospitals

- regional referral hospitals

- general (district) hospitals

Within the district, there are health centers with varying capabilities:

Health Center I and II: the most basic healthcare facility. Not suitable for serious medical conditions [11];

Health Center II and IV: the most comprehensive medical services.

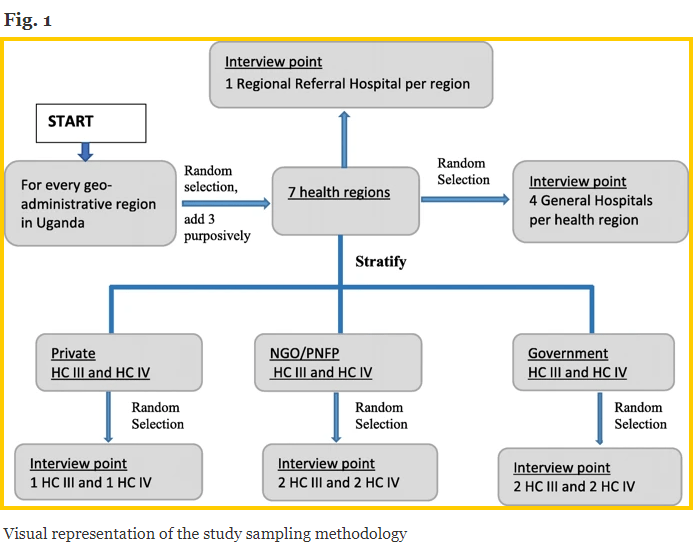

The Makerere University obtained a sampling frame of all health facilities in Uganda from MoH and stratified the list by health regions. The health regions were further grouped into Uganda’s 4 geo-administrative regions [12] (i.e., North, East, West, and Central) to ensure each geo-administrative region was represented in the sample. Within each geo-administrative region, the study team randomly selected one health region (Fig. 1 – below).

They purposively included three additional health regions: Arua health region in West Nile since it hosts a large refugee population, which may impact access and availability of EMS. Another is the Karamoja health region since it has a history of conflict and has historically been disadvantaged with poor access to all social services. The third is the Kalangala district which is made up of 84 islands and therefore has unique transport access challenges.

The Makerere University team of researchers grouped all HCs in the selected health regions by ownership (i.e., government-owned, private not-for-profit/non-governmental organization (PNFP/NGO), and private for-profit HCs). For each health region, they randomly selected 2 private for-profit health centers (i.e., 1 HC IV and 1 HC III), 4 PNFP/NGO health centers (i.e., 2 HC IV and 2 HC III), and 4 government-owned health centers (i.e., 2 HC IV and 2 HC III). Where a private-for-profit or PNFP/NGO HC III or HC IV did not exist in the selected health regions, they filled the slot (s) with a government-owned HC III or HC IV.

Their sampling strategy resulted in a sample size containing 7 regional referral hospitals, 24 general (district) hospitals, 30 HC IV and 30 HC III. In addition, Kampala District was considered a special region due to its status as the capital city with a high concentration of health resources. Out of the three RRHs (i.e., Rubaga, Nsambya, and Naguru) in the city, one RRH (Naguru) was added to the study sample.

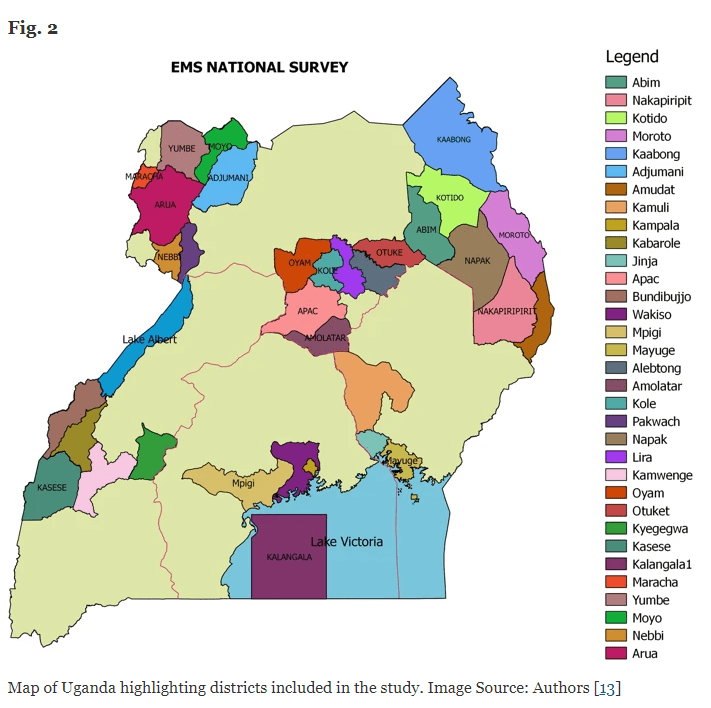

Additionally, they included the police as pre-hospital care providers because they are often the first responders at casualty scenes and provide transportation to victims. The study is a cross-sectional national survey that includes 7 health regions, 38 districts (Fig. 2) [13], 111 health facilities, and 52 pre-hospital care providers. From each of the 38 districts, researchers interviewed one senior district officer, most often the District Health Officer who is a district-level decision-maker, and a total of 202 key personnel involved in EMS and acute health facility care.

Ambulance equipment and trained professionals lack in Uganda: data collection

The researchers from the Makerere University adapted the WHO Emergency Care Systems assessment tool [14] developed by Teri Reynolds and others [10]. This helped them to collect data on EMS at the pre-hospital and health facility levels. The tool comprised of checklists and structured questionnaires, which assessed six health system pillars: leadership and governance; financing; information; health workforce; medical products; and service delivery. They also reviewed reports from previous EMS studies in Uganda [7,8,9] and filled gaps in information thanks to a key informant face to face interview with a senior MOH official.

EMS in Uganda: Results overview on ambulance equipment and trained professionals lack

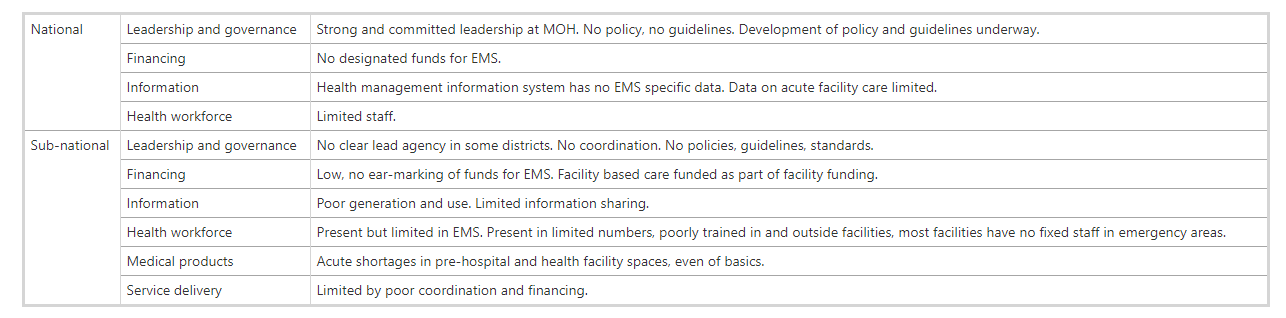

The following table summarizes the results found in the various fields both at national and sub-national levels. More detailed results at the links at the end of the article.

Data on EMS in Uganda: discussion

Uganda turned out to have a deep lack of national policy, guidelines, and standards in the emergency medical field. This lack is reflectin on any sector of the healthcare field: funding; medical products, and coordination.

Emergency areas in health facilities lacked the most basic ambulance equipment and medicines both to monitor and to treat various emergency medical conditions. This severe lack of equipment and medicines was observed at all levels of the health system. Although, private health facilities and ambulances were relatively better equipped than government ones. The limited availability and functionality of ambulance equipment for responding to emergency medical conditions meant patients were getting very limited care in the pre-hospital phase, and then being transported to health facilities that were only marginally better equipped to manage their acute events.

Ambulance services were plagued by poor equipment, coordination and communication. At least 50% of the EMS providers interviewed reported that they never notified health facilities prior to transferring emergencies there. That hospitals, including regional referral hospitals, did not have EMS available 24 h a day. Indeed, bystanders and relatives are often the only ones to medically assist patients. And police patrol vehicles were the commonest (for 36 of 52 providers) mode of transporting patients in need of emergency care.

The study had defined an ambulance as an emergency vehicle providing both emergency transportation and care while in the pre-hospital space, it meant that the majority of pre-hospital providers did not have ambulances, but they were providers of emergency transportation. Moreover, at every level, there was evidence of insufficient financing for EMS.

The limits of this study are measurement errors from reliance on self-reports for some of the outcomes (e.g., data use for planning). However, the majority of the key outcomes (availability and functionality of medical products) in the study were measured through direct observation. The researchers’ findings corroborate those from other studies using a similar methodology which found a lack of leadership, legislation and funding as key barriers to the development of EMS in developing countries [16].

The one reported in this article was a national survey and therefore the findings could be generalized to the whole of Uganda. The findings could also be generalized to other low- and middle-income countries within Africa that have no EMS systems [1] and can, therefore, be used to guide efforts aimed at improving EMS systems within these settings.

In conclusion…

Uganda has a multi-tiered system of health facilities to which patients can go for medical care. However, from the findings above many could ask ‘Does Uganda have an EMS?’. We have to specify that this study was conducted at a time when there was no EMS policy, no standards, and very poor coordination at national and sub-national levels.

According to Makerere University findings, it, therefore, seems prudent to conclude that there was, in fact, no EMS, but a number of important components in place which could be restructured as a starting point for the establishment of the system. This would explain the reason for the ambulance equipment and properly trained personnel lack. However, there was a process underway to develop policies and guidelines for the establishment of the EMS.

REFERENCES

- Mistovich JJ, Hafen BQ, Karren KJ, Werman HA, Hafen B. Prehospital emergency care: Brady prentice hall health; 2004.

- Mould-Millman N-K, Dixon JM, Sefa N, Yancey A, Hollong BG, Hagahmed M, et al. The state of emergency medical services (EMS) systems in Africa. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2017;32(3):273–83.

- Plummer V, Boyle M. EMS systems in lower-middle income countries: a literature review. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2017;32(1):64–70.

- Hirshon JM, Risko N, Calvello EJ, SSd R, Narayan M, Theodosis C, et al. Health systems and services: the role of acute care. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:386–8.

- Mock C, Lormand JD, Goosen J, Joshipura M, Peden M. Guidelines for essential trauma care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

- Kobusingye OC, Hyder AA, Bishai D, Joshipura M, Hicks ER, Mock C. Emergency medical services. Dis Control Priorities Dev Countries. 2006;2(68):626–8.

- Bayiga Zziwa E, Muhumuza C, Muni KM, Atuyambe L, Bachani AM, Kobusingye OC. Road traffic injuries in Uganda: pre-hospital care time intervals from crash scene to hospital and related factors by the Uganda police. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot. 2019;26(2):170–5.

- Mehmood A, Paichadze N, Bayiga E, et al. 594 Development and pilot-testing of rapid assessment tool for pre-hospital care in Kampala, Uganda. Injury Prevention. 2016;22:A213.

- Balikuddembe JK, Ardalan A, Khorasani-Zavareh D, Nejati A, Raza O. Weaknesses and capacities affecting the Prehospital emergency care for victims of road traffic incidents in the greater Kampala metropolitan area: a cross-sectional study. BMC Emerg Med. 2017;17(1):29.

- Reynolds TA, Sawe H, Rubiano AM, Do Shin S, Wallis L, Mock CN. Strengthening health systems to provide emergency care. Disease Control Priorities: Improving Health and Reducing Poverty 3rd edition: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2017.

- Acup C, Bardosh KL, Picozzi K, Waiswa C, Welburn SC. Factors influencing passive surveillance for T. b. rhodesiense human african trypanosomiasis in Uganda. Acta Trop. 2017;165:230–9.

- Wang H, Kilmartin L. Comparing rural and urban social and economic behavior in Uganda: insights from mobile voice service usage. J Urban Technol. 2014;21(2):61–89.

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System 2018. Available from: http://qgis.osgeo.org.

- World Health Organization. Emergency and trauma care Geneva, Switzerland. 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencycare/activities/en/.

- Hartung C, Lerer A, Anokwa Y, Tseng C, Brunette W, Borriello G. Open data kit: tools to build information services for developing regions. In: Proceedings of the 4th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies and Development. London: ACM; 2010. p. 1–12.

- Nielsen K, Mock C, Joshipura M, Rubiano AM, Zakariah A, Rivara F. Assessment of the status of prehospital care in 13 low-and middle-income countries. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2012;16(3):381–9.

AUTHORS

Albert Ningwa: Department of Disease Control and Environmental Health, Makerere University School of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda

Kennedy Muni: Department of Epidemiology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA

Frederick Oporia: Department of Disease Control and Environmental Health, Makerere University School of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda

Joseph Kalanzi: Department of Emergency Medical Services, Ministry of Health, Kampala, Uganda

Esther Bayiga Zziwa: Department of Disease Control and Environmental Health, Makerere University School of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda

Claire Biribawa: Department of Disease Control and Environmental Health, Makerere University School of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda

Olive Kobusingye: Department of Disease Control and Environmental Health, Makerere University School of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda

READ ALSO

EMS In Uganda – Uganda Ambulance Service: When Passion Meets Sacrifice

Uganda For Pregnancy With Boda-Boda, Motorcycle Taxis Used As Motorcycle Ambulances

Uganda: 38 New Ambulances For The Visit Of Pope Francis

SOURCES

BMS: BioMed Central – The state of emergency medical services and acute health facility care in Uganda: findings from a National Cross-Sectional Survey

Peer Reviews: The state of emergency medical services and acute health facility care in Uganda: findings from a National Cross-Sectional Survey

School of Public Health College of Health Sciences, Makerere University

The WHO: emergency care