Life-threatening situations: violent reaction during an emergency survey

The incident described in this case study occurred in a rural county. It can happen that the situation can turn out of control without notice and in case of situation degenerates, the police would help in solving the situation.

The incident described in this case study occurred in a rural county. It can happen that the situation can turn out of control without notice and in case of situation degenerates, the police would help in solving the situation.

Life-threatening situations are frequent and common for EM practitioners. The #AMBULANCE! community started in 2016 analyzing some cases. This is a #Crimefriday story to learn better how to save your body, your team and your ambulance from a “bad day in the office”!

Life-threatening situations: violent reaction during an emergency survey

“I have worked as an EMT (Emergency Medical Technician) on an ambulance in Canada for 4 years. The county where the case occurred has 2 ambulances employed to cover approximately 3400 km2 of terrain. Average response times can vary greatly, from a few minutes to 40 minutes, based on the distance to scene of call and ease of accessibility (the majority of roadways are unpaved).

One ambulance is staffed and equipped to an ALS (Advanced Life Support), while the other is staffed and equipped to a BLS (Basic Life Support) level. The ALS unit is manned by a Paramedic and EMT and is able to perform all ACLS (Advanced Cardiac Life Support) treatments as defined by the American Heart Association.

The BLS unit is staffed by 2 EMTs, and cannot perform ACLS, but is able to provide a variety of other treatments aimed around initial response (such as IV’s, oxygen therapy, supraglottic airway placement, cardiac monitoring and defibrillation). The BLS unit may also activate the ALS unit for back up, and has the ability to consult with a physician via telephone.

This event was initially attended by the BLS unit, with ALS unit arriving later for back up.

Protocols for cardiac arrest and for discontinuing resuscitation included below for reference:

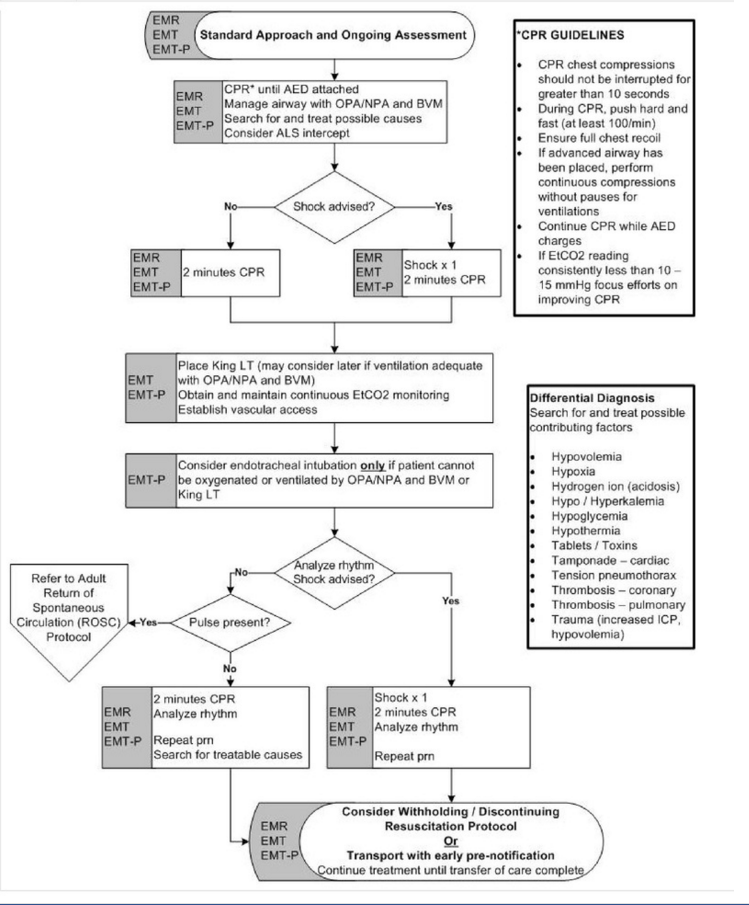

- Cardiac arrest protocol

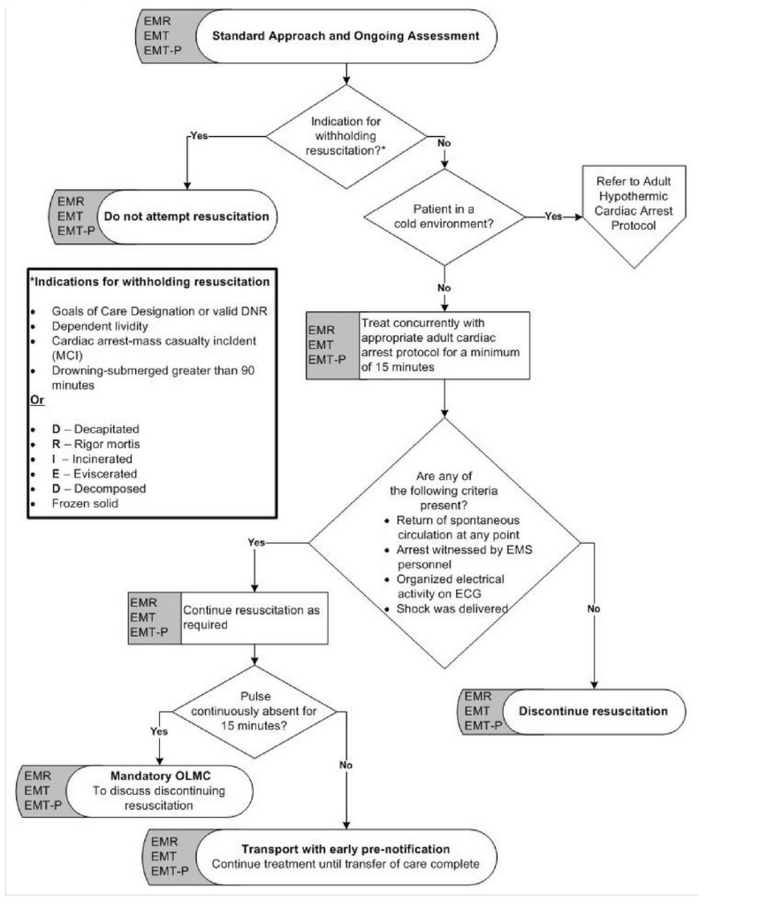

2. Discontinue Resuscitation Protocol

2. Discontinue Resuscitation Protocol

It occurred at one of the several Indian Reservations within the county. Reservations are federally designated lands that have been set aside for the use of a specific band (or tribe) of aboriginals. They exist and operate with some autonomy from the general population. I am by no means an expert on aboriginal relations in Canada, and it is a rather contentious matter in my country. So I hope only to convey how this influenced the incident that occurred, and how it bared on the security of the situation.

Life-threatening situations in Canada: social conditions of aboriginals

Social conditions vary between reservations, but on average they are much poorer than the general population. Just some brief statistics to highlight this point:

- The unemployment rate on reservations is approximately 3 times higher than the national average

- 61% of young aboriginal-adults do not complete high school, and 43.7% do not attain any educational certificate, diploma or degree

- Rates of violent crime committed on reserves were as of 2004: eight times higher for assaults, seven times higher for sexual assaults and six times higher for homicides than rates in the rest of Canada

- The rates of mental health problems are significantly higher among aboriginal peoples than in the general population, the suicide rate being 2.1 times higher than non-aboriginal Canadians

The location of the incident reflected many of these statistics. It has a disproportionate amount of poverty, violence, mental health, and addiction issues.

Canada also has a long history of colonization, that historically involved government enforced assimilation of aboriginals. Consequently, there are enduring attitudes of distrust towards the government on reservations.

Life-threatening situations: the case

As EMS and other first responders are associated as government employees this can create a barrier to providing care. To briefly put it, wearing a uniform is sometimes an open invitation to hostility.

THE CASE – We responded to an unknown ‘man down‘ situation on a remote Indian reservation. While en route updates provided on patient status were confusing, and incoherent. The best information available indicated a 50-year-old female was found unconscious by family. Multiple units had been dispatched to this event, although due to the remoteness and inaccessibility they would be about 20 minutes behind us.

On the scene, we discovered the patient was in fact in cardiac arrest, and CPR had been started by family. We continued resuscitation efforts while awaiting back up. During this time more information became available from the family, with evidence indicating the patient was unviable With the nearest hospital 45 minutes away, the patient having received CPR for 30 minutes, and confirmed asystole for 20 minutes–our protocols allowed for the cessation of resuscitation. We consulted with a physician via phone, and agreed to discontinue CPR, and declare death on the scene.

The second unit had arrived at this time. We contacted the police as per the standard procedure for an unexpected death at home. The family of 6 gathered in a common room on the other side of the house to mourn. As we gathered our equipment, I heard some bumping and movement coming from a bedroom directly across from the room where the dead body lay. My partner at this time told me that while we were working the code, he had seen a large man stick his head out from this bedroom to watch very briefly. The man had then retreated back into the room and shut his door. It was at this point we realized, that we had an individual on scene unaccounted for.

We found this man’s behaviour peculiar in several ways. The fact that he was so near to the body, but when we had initially arrived, he was not among any of the family members attempting to provide assistance or helping with CPR in any way. Secondly that he choose to segregate himself from the rest of the grieving family. Thirdly that he made no attempt to disclose his presence to us. My partner and I discussed it briefly without trying to draw too much attention to our conversation. Although we found the situation odd, we couldn’t find anything overtly suspicious or establish any definite malicious intent on behalf of this man–so we agreed to just remain extra vigilant and maintain visual contact with the body and each other at this time.

After the initial shock of death declaration had sunk in a bit, I went to talk to the family about the deceased. I had a few standard routine questions about proof of identity and any evidence of illness or obvious cause of death. The family, although grieving, were very cooperative and open to my presence and questions. However, when I asked about the man hiding in the back bedroom, they became very hesitant to provide information on him. They denied knowing his surname and would not positively state what his relationship was to them or the deceased.

They refused to approach his bedroom, and stated it was ‘best to leave him alone’. It was at this time while interviewing the family, I noticed a radio scanner quietly monitoring the police channels on a kitchen shelf. I have frequently come across radio scanners in private residences on the reserve, but in my experience, it usually indicates someone within the house is attempting to avoid police contact (either due to outstanding arrest warrants or due to involvement in illicit activities). I also noticed the TV was displaying feeds from security cameras surrounding the property. Such security measures are abnormal and inconsistent for a small, low income, rural household.

At this time the second ambulance arrived. I alerted them that there was evidence of suspicious circumstances on the scene. I asked them that although there was nothing they could do, to remain on scene with us for safety in numbers until police arrived. They full-heartedly agreed. I then radioed my dispatcher for an ETA for police. However, because police and EMS use 2 separate communication centres, I knew that even getting this information would take time a lot of time.

While waiting for the police, the individual hiding in the back room came forward, introduced himself as the husband of the deceased, and aggressively instructed us to leave the property immediately. He also insisted on having immediate access to the body. I attempted to calmly explain our present and the procedures that would now occur. I also clearly identified the police were on their way to scene. He had no interest in listening, continued to yell over me with swears while I talked. He then returned to his bedroom and became quiet.

After maybe 5 minutes he came back out and repeated the exact same routine. When he returned to his bedroom, I asked one of the members of the other crew to attempt to get a direct line to police. And despite my best efforts to defuse the situation, on the third time, he began pushing me into the wall and yelling expletives. He gave me explicit instructions that I had to leave in the next two minutes or harm would come to me. He said a ‘world of hurt was coming my way’ and that ‘I wouldn’t know what hit me’. He then spat on my boots, and returned to his bedroom, again. At this time I radioed a code, indicating an emergency response of the police was required to scene.

When the police arrived this individual became immediately subdued and submissive, transforming into a completely different personality. He calmly exited his room when instructed to by police. He was polite and respectful to the officer and even apologized to me for his actions. He blamed his aggressive behaviour on the distress of witnessing his wife’s passing.

We later reviewed the call with the police officers involved. They reported to us that this individual had in the past been incarcerated for violent crimes. He had admitted to the police that his aggression to EMS had come from his incredible feeling of apprehension. He had been absolutely convinced, at the time, that with his past record he would be presumed guilty in the death of his wife. To my knowledge, the wife passed from medical complications.

ANALYSIS – This call was interesting on several levels, although at the time it was incredibly scary for me. The pushing was very minor, I was not physically harmed by it. The threats and swearing were not anything I had not heard before. The spitting was gross but didn’t present any real biohazard danger. But the combined stress of it all did impact me and undermined my confidence in dealing with death declarations for some time.

There were several lessons learned from this incident:

Early Police Activation & Complacency

Early police activation is essential in remote and rural settings. Looking back, when the initial dispatch information became conflicting and confusing, I should have been more suspicious. It would have been perfectly acceptable to ask for police to attend this call while we were still en route. Early police activation has always been advocated in our organization, and I knew this at the time of the incident. It was more just a matter of complacency, that over time I had become accustomed to responding to calls with little or conflicting information (with little or no consequence).

Defining Acceptable Risk

Although we are constantly told our top priority is our own safety, in truth for frontline workers, it can be a struggle between absolute security and what is actually operationally feasible. I found on this call what most influenced my judgement of what was acceptable risk was both my experience, as well as my inexperience. My previous experience led me to be suspicious of the man from his initial actions on scene (when he hid in the bedroom from us), and the way his family interacted with him. It also led me to suspect a criminal element when noticing the radio scanner and security equipment. But the truth was, although I noticed that risk was climbing, I continued to feel it was within the acceptable threshold probably because of my inexperience. My inexperience let my judgement of the situation be influenced by a lot of ideas that were centred more on my peers’ perceptions and expectations, rather than what was actually going on. Some of the thoughts that were going on in my head were:

- I can’t get a hold of the police. But I can’t use the emergency code radio code, that is for serious situations only. Like when physical violence has already occurred towards a practitioner, right?

- The police are responding from far away. They could be engaged in other priorities. I can wait.

- So what if the guy is acting odd. I don’t need to stir up a lot of trouble, just because I think he is ‘off’

I think the only real way to combat this kind of ideation is to build better peer support, between co-workers and with peers on a multi-agency level. It is not enough to train that ‘safety is our top priority’. We need to really expand the understanding further to include the fact that everyone’s risk threshold will be different. But, regardless of that, however an individual defines their own threshold it will be supported by their peers and by the police.

Familiarization with the Grief Process

Our training did not prepare us to deal well with this particular incident. Death declaration is not a subject that is generally covered in the EMT syllabus. I had 3 hours of training in this area, many of my coworkers have none. We were always instructed that it was the responsibility of the police to handle, and not something we needed to know much about. This works well for metropolitan areas, but in rural communities, it is not uncommon for family or associates of the deceased to arrive on scene before police is able to.

I believe this deeply affected our actions during the incident. The combined strain of having to declare death and support the grieving family, but not really knowing how to, really led to us be uncertain on how to judge the man’s actions and behaviour. It also led us to underestimate the potential for rapid escalation towards violence.

After this incident, I discussed it with my co-workers and found there was an overwhelming interest in my decision to pursue training in this area. We reached out to victim services (a subunit of the police that supports victims of crime or tragedy) and arranged for a training session on best practices for death declaration, family notifications, grief reactions, and the police processes involved with an unexpected death at home.

In the last year, the issue of family presence during resuscitation (FPDR) has become an emerging topic in our healthcare system. Some major organizations (such as the American Heart Association) encourage FPDR, reporting it is a basic right and aiding significantly in the grieving process. It is still not a common practice, and only one major trauma center in our area is actively encouraging FPDR. It was discussed at this year’s clinical symposium for EMS, and generally found to be a beneficial practice, although the majority of practitioners were uncertain how to best implement it without compromising on patient treatment or crew safety.

In conclusion death declaration, next of kin notification, and overall dealing with grief reactions are not a well-established practice in our EMS system. But recently there is some initiative to correct that.