Endotracheal intubation in paediatric patients: devices for the supraglottic airways

Endotracheal intubation (ETI) in children is thankfully rare and our first pass success rate could definitely do with some improvement

It is difficult to compare the efficacy of various advanced airway techniques in children.

There are ethical implications, of course, but also marked differences in ages and in the potential aetiology of the arrest.

There is often time to talk with the intensive care team and make a plan based on the best airway for that given situation.

Similarly, the operating theatre, home of many an airway trial, is a very different environment.

We’ll look at advanced airways in cases of cardiac/respiratory arrest.

Be mindful there will always be a difference in timing and skill set between out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) to in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA).

There are few actual studies comparing the advanced airway treatments used during cardiac arrest management in children.

There are even fewer studies surrounding the use of supraglottic airways (SGAs) in children. Most of these are observational studies.

ILCOR currently recommends endotracheal intubation (ETI) as the ideal way to manage an airway during resuscitation

They also state that supraglottic airways are an acceptable alternative to the standard bag-valve-mask ventilation (BVM).

There are very few clinical trials in children on which these recommendations are based (and certainly none of rigorous design in the last 20 years).

Due to this lack of evidence, they commissioned a study as part of the Paediatric Life Support Task Force.

Lavonas et al. (2018) carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis on the use of advanced airway interventions (ETI vs SGA), compared to BVM alone, for resuscitation of children in cardiac arrest. Only 14 studies were identified.

12 of these were suitable for inclusion in the meta-analysis.

They were mostly focused on OHCA. There was a high risk of bias and so the overall quality of evidence was in the low to very low range.

The key outcome measure was survival to hospital discharge with a good neurological outcome.

The analysis suggested that both ETI and SGA were not superior to BVM.

So now, let’s cover some of the literature on the use of supraglottic airway devices. These are mostly based on studies in adults.

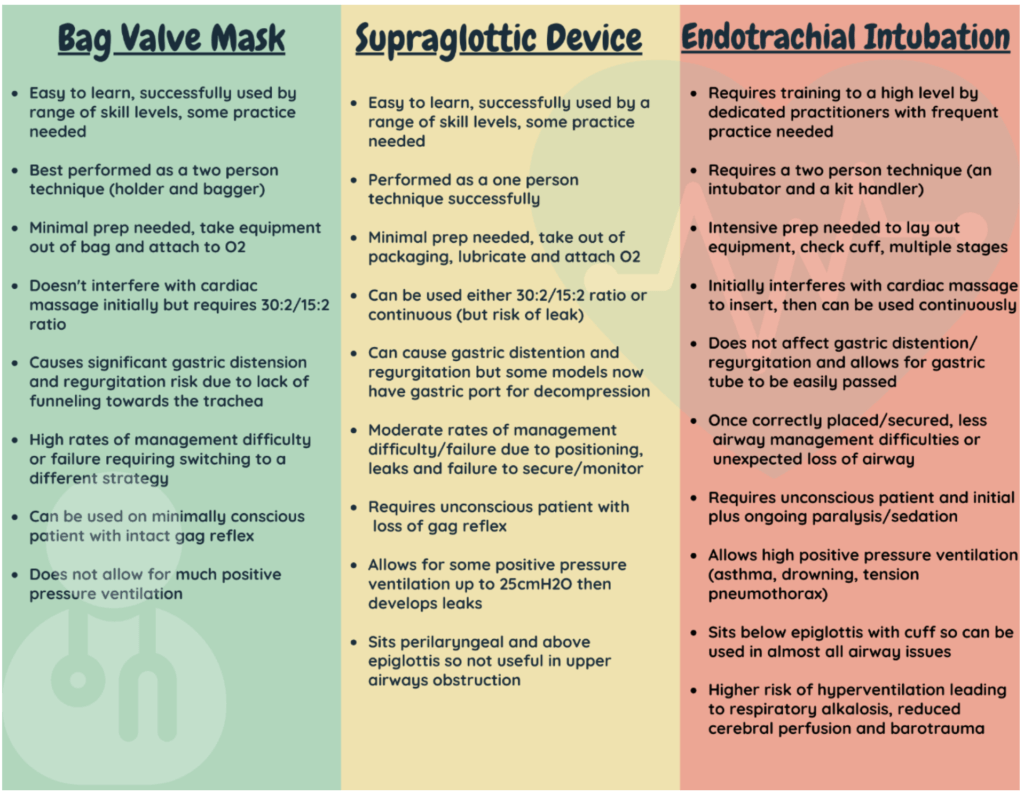

The ideal ventilatory device

- …is easy to set up and insert by anyone so it doesn’t matter what the make-up of the team is

- …is quick to set up and quick to insert. This reduces the time taken away from other important tasks and allowing that all-important ‘bandwidth’

- …allows for minimal risk of aspiration

- …provides a tight seal to allow for high airway pressures if needed

- …is sturdy enough that the patient cannot bite through it and cut off their own oxygen supply

- …provides an option to decompress the stomach via the same device

- …has minimal risk of accidental misplacement or loss of airway once inserted

If this sounds too good to be true, it is. No one device combines all of these essential features.

This leaves us deciding which is most suited to the patient in front of us.

It is very difficult to compare SGAs with endotracheal tubes (ETT).

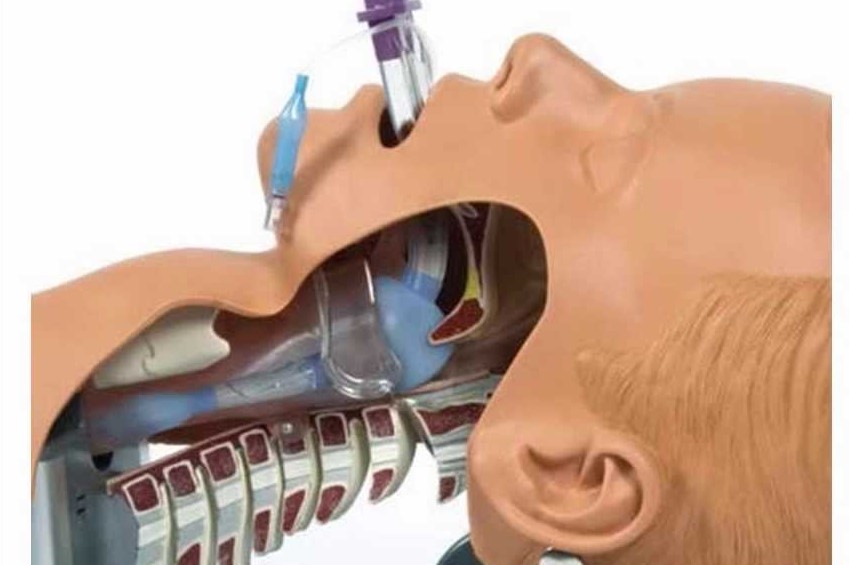

An ETT is a ‘definitive airway’ that provides protection against aspiration.

This does not mean that SGAs are a ‘lesser’ option.

An SGA is still an ‘advanced airway’ and more effective than using a bag-valve-mask technique.

It is important to remember that advanced airways have their pros and cons.

Whilst they may improve a patients’ likelihood of survival with good neurological recovery, there can be associated complications.

The science behind supraglottic airways

So what does the science say? There are few trials in children but there have been several seminal papers released on advanced airway techniques in adults. Whilst not directly related to children, they do raise some interesting points of comparison between devices.

This multicentre, cluster randomised trial, was conducted by paramedics across four ambulance services in England. It compared supraglottic devices to tracheal intubation in adult patients with OHCA looking at their effect on functional neurological outcome.

This study only included patients over the age of 18.

They found no statistically significant difference in 30-day outcome (the primary outcome measure) or in survival status, rate of regurgitation, aspiration or ROSC (secondary outcomes).

There was a statistically significant difference when it came to initial ventilation success.

Supraglottic airways required less attempts, but their use also lead to an increased likelihood of the loss of an established airway

So what does this mean? The main concern that gets bandied around when discussing SGAs is the higher risk of aspiration. If there was no difference in risk, would that change your mind?

This was a multicentre, randomised clinical trial in France and Belgium looking at OHCA over a 2-year period. Again this study enrolled adults over 18 years old.

They looked at the non-inferiority of BVM vs ETI with regard to survival with favourable neurological outcome at 28 days.

Responding teams consisted of an ambulance driver, a nurse and an emergency physician.

The rate of ROSC was significantly greater in the ETI group but there was no difference in survival to discharge.

Overall, the study results were inconclusive either way.

If survival to discharge is unaffected, should we all be spending time training and maintaining competency or should endotracheal intubation be kept only for those who practice it regularly in their day job?

This cluster-randomised, multiple crossover design was carried out by paramedics/EMS across 27 agencies.

It looked at adult patients receiving either laryngeal tube or endotracheal intubation and survival at 72 hours.

Again, they only included adults over 18 with non-traumatic cardiac arrest.

They found a ‘modest but significant’ improved survival rate in the LMA group and this correlated with a higher rate of ROSC.

Unfortunately, this trial included a lot of potential bias and the study design may not be robust enough to back up the level of difference.

Could the survival rate be explained by first-pass success and less time spent ‘off the chest’ during initial resuscitation? No study is perfect. Always critically appraise for yourself and check if study results are applicable to your local population and own practice before changing anything.

More questions than answers

After reading the science (and please do go take a deeper dive into those papers and appraise them for yourselves), let’s tackle some common queries.

SGAs are so easy you can just whack it in and done!

No. Getting the SGA in is only the first step. Even then, you need to be sure you have picked the appropriate size and assessed for leaks. SGAs are much more likely to become dislodged and lead to an unexpected loss of airway. Generally, we are not as meticulous about securing them as we should be. Ideally, use a tube tie to secure it in place and monitor the position (in relation to the teeth). Some SGAs have a black line on the shaft that should line up with the incisors (beware this may only be present in the larger sizes). Just like ETTs, they require you to check for adequate ventilation via auscultation, ETCO2 and listening for an obvious leak.

It’s okay if there is a leak at the start as the gel will mould as it heats up

No. There is no evidence to suggest the shape of i-gels (this is usually the model clinicians are referring to in this instance) will mould to the inside of the larynx. Researchers have tried heating up the material and there is no statistical change in the leak. If you do have a significant leak, consider re-positioning, swapping out for a different size or using a different model. You may find a small leak that disappears over time. Over time, the airway jiggles around and sits better.

You should always decompress the stomach when you put in an LMA

Possibly. This is not routinely found in guidelines as it is seen as more of a fine-tuning procedure. It can take time and resources away from other critical tasks (such as chest compressions, IV access, optimal ventilation) but if you have the resources to do so, without affecting the basics of good resuscitation care, then it is a good option if ventilation is not as optimal as it could be. This is particularly important in children. We know that they are at higher risk of diaphragmatic splinting from overzealous ventilation so the early insertion of a nasogastric tube can really improve things.

Laryngoscopy should be used before every SGA insertion

Possibly. Some places have started to mandate laryngoscopy because they have missed obstruction by a foreign body, or to allow better suctioning and improve the passage for insertion. There is an argument that the SGA may sit better if inserted with the aid of a laryngoscope as, in a number of cases, it hasn’t been inserted deeply enough. Laryngoscopy is a complex skill, that takes regular practice and comes with its own challenges (damage to mouth/teeth, additional time taken, higher skill set needed).

Once inserted, SGAs can be used alongside continuous chest compressions

Possibly. This really needs to be considered on a case-by-case basis. SGAs are an advanced airway and can be used with continuous chest compressions to increase cerebral perfusion pressures. It is up to the individual clinician to monitor and decide if the ventilatory support they are giving is adequate during active compressions. In cases where the arrest is secondary to hypoxia (as in many paediatric arrests) it may be easier, and more useful, to continue with a 30:2 or 15:2 ratio to ensure good tidal volumes are reaching the lung. Some studies have shown little difference comparing the 30:2 approach to continuous ventilation.

Read Also:

Successfull Intubation Practice With Succinylcholine Versus Rocuronium

Tracheostomy During Intubation In COVID-19 Patients: A Survey On Current Clinical Practice

Tracheal Intubation: When, How And Why To Create An Artificial Airway For The Patient