Solving the Problem of Delivering Oxygen during Needle Cricothyroidotomy

This article was published first on Emergency News Medicine

Dr. Solis is an emergency physician with the Huntsville Hospital System in Hunstville, AL, and an occasional assistant professor at Georgia Regents University, where he works withLarry Mellick, MD, who shot the video. Dr. Mellick is a professor of emergency medicine and pediatrics at Georgia Regents University in Augusta, the former chairman of emergency medicine at Georgia Regents Health System, and a professor of emergency medicine and pediatrics at Georgia Regents Medical Center and Children's Hospital of Georgia.

When faced with a “can’t intubate, can’t oxygenate” crisis, the decision to move to a surgical airway must be made rapidly and deliberately. A surgical cricothyroidotomy is debatably the better approach in these situations, but a needle cricothyroidotomy may sometimes be indicated. It may be easier to perform in a very small child, for example, and although it is probably less than ideal in an adult, a rapid needle cricothyroidotomy may provide an oxygenation bridge that will prevent a critically hypoxic patient from arresting until a more definitive airway is secured.

Cricothyroidotomy with an over-the-needle catheter itself may be easy to perform, but the more technically and logistically difficult part of the procedure remains how to deliver oxygen through a 14G catheter. In the absence of a proper percutaneous transtracheal catheter oxygenation setup such as an Enk oxygen flow modulator or a Roy Rapid-O2 device, many different improvised setups have been described. These all have advantages and disadvantages, but the main disadvantage is that they involve putting together parts that were not designed to play nice with each other.

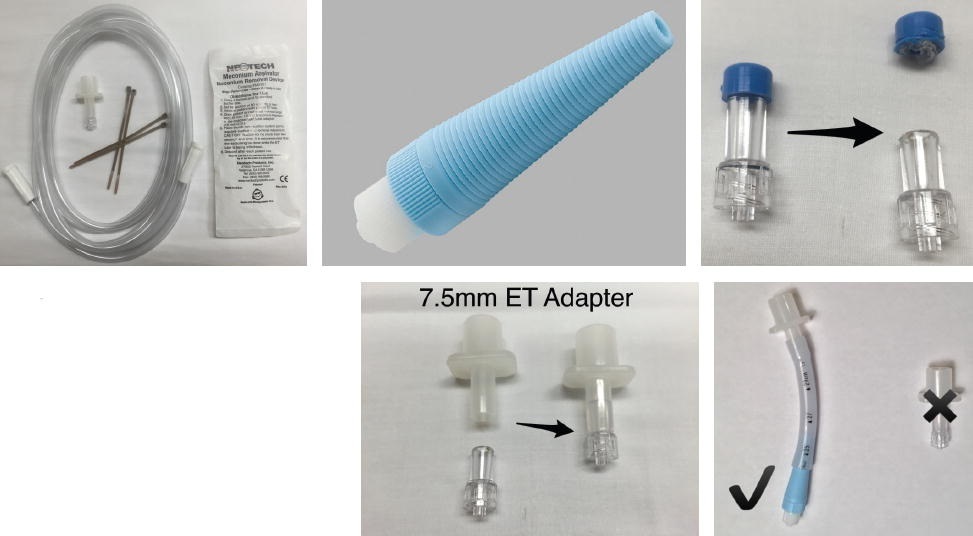

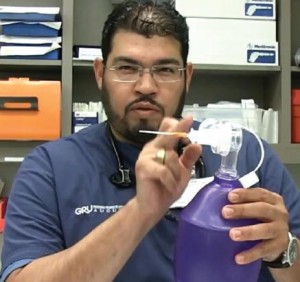

I explain this novel setup that may be effective in providing percutaneous transtracheal catheter oxygenation in a video posted onEMN‘s website. (http://bit.ly/1EluCy0.) The system, consisting of large-bore suction tubing and a meconium aspirator, plus-or-minus zip ties, is connected to the oxygen regulator Christmas tree. A maximum flow rate can then be set at the oxygen regulator (typically 1 liter per minute per year of age to a maximum of 15 liters per minute,) with further regulation of flow and delivery of breaths by occlusion of the side port on the meconium aspirator. The large diameter of the exhalation port (the same side port on the meconium aspirator) should allow for adequate exhalation, although the limiting factor here will likely be the caliber of the catheter.

I requested FOAM community feedback on Twitter, YouTube, and Google+, and the PHARM Podcast comments section has helped improve on the concept, with a few notable changes. The use of zip ties to secure the tubing to the regulator and to the aspirator is likely unnecessary. (Thank you, @ketaminh, @TBayEDguy, and @MikeSteuerwald.) The system coming apart under excessive pressure may provide an extra layer of safety over providing too much pressure to the patient.

The other major change came at the suggestion of Scott Weingart, MD (@emcrit), who, like many others, was concerned about the feasibility of putting together the homemade ETT to male Luer lock adapter. His brilliant solution is to use a male Luer lock to Christmas tree adapter, which is commercially available and designed for this very purpose (Multipurpose Tubing Adapter, Cook Medical;http://bit.ly/1KLe341.) Attach a cut-off ETT to the Christmas tree end and screw the Luer lock end into the catheter. The meconium aspirator can then be connected to the ETT adapter, as shown in the video and oxygen can be delivered by occluding the port of the meconium aspirator as described.

The multipurpose tubing adapter from Cook Medical is a male Luer lock to a universal taper. (http://bit.ly/1KLe341.)

The advantages of this setup is that all parts are stock, and nothing has to be manufactured; it just has to be put together in the right order. Another advantage of the multipurpose tubing adapter is that, like the meconium aspirator, it has several uses because it can be used for draining fluid after paracentesis or thoracentesis and for irrigating through a chest tube as may be needed in the severely hypothermic patient.

My recommendations, still being studied and revised, are: