A guide to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease COPD

Chronic bronchopneumatic disease is a major health problem: predisposing factors contributing to the disease include smoking, environmental pollutants, industrial exposure and other lung infectious processes

The triad of chronic bronchopneumatic diseases, simply called COPD, includes asthma, bronchitis and emphysema

Even though it is so commonly treated by EMS, there have been misconceptions created over the years concerning the initial treatment of COPD patients in the prehospital environment.

Our failure to understand the different disease concepts involved can reduce our ability to identify and treat these patients, safely and effectively.

It is important to know COPD inside and out; you will see it often.

BPCO (Chronic bronchopneumatic disease): Chronic Bronchitis “The Blue Bloater”

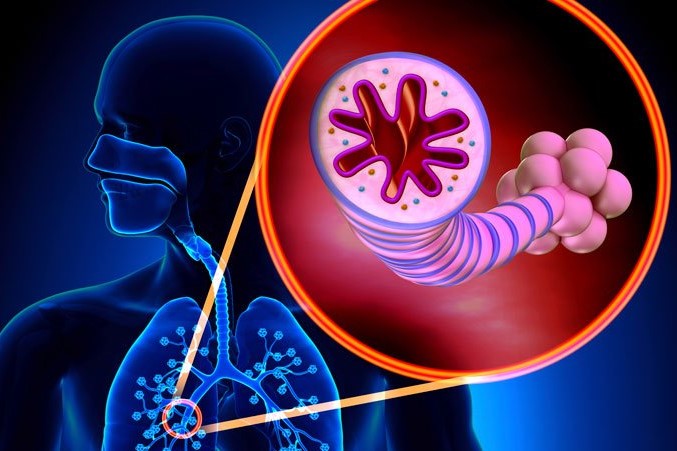

Chronic bronchitis is the more common form of COPD.

It is characterized by air being trapped within the lungs due to the overproduction of mucus that plugs up the airways.

Inhalation of irritants (such as cigarette smoke) irritates the airways and result in inflammation.

Inflammation promotes the mucus procuring glands that produce protective mucus to enlarge and multiply.

Increased mucus production eventually results in obstruction of the small airways and chronic inflammation due to the overgrowth of bacteria.

The vicious cycle of inflammation from irritants and inflammation from chronic bacterial infection leads to a dramatic increase in COPD symptoms.

This cycle leads to irreversible damage to the larger airways (bronchiectasis).

These changes are dangerous as the air-trapping that COPD leads to reduces oxygen (O2) levels and increases carbon dioxide (CO2) levels in the body.

The accumulation of CO2 is the most dangerous as high CO2 levels lead to decreased mental status, decreased respiration, and eventual respiratory failure.

Emphysema “The Pink Puffer”

Emphysema is another form of COPD.

It leads to the same end result as chronic bronchitis but has a very different etiology.

Irritants damage the thin-walled air sacks (the alveoli) that are critical to the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide.

As these air sacks are destroyed the ability to absorb O2 and expel CO2 gradually decreases over the course of decades.

As the alveoli are destroyed the spring-like lung tissue loses much of its “springiness” that the lungs rely on to squeeze to air during exhalation.

Eventually, this decrease in springiness makes exhalation very difficult, even though air has no issue entering the lungs.

This is combined with an inability for O2 and CO2 to be exchanged due to the destruction of the alveoli as above.

This process leads to “obstruction” by making it impossible to exhale fast enough to allow fresh air to enter.

The body will compensate for this by using the muscles of the ribcage, neck, and back to put pressure on the lungs.

Helping them to contract during exhalation and force air out.

This results in a dramatic increase in the amount of energy required to breathe.

This energy requirement leads to the very skinny and sickly appearance that many patients with emphysema have.

Chronic bronchopneumatic disease: The Reality of COPD

In reality, all patients with COPD have some chronic bronchitis and some emphysema.

- Chronic bronchitis prevents air from entering the lungs effectively

- Emphysema prevents air from leaving the lungs effectively

- Both result in decreased oxygenation of the blood (hypoxia)

- Both increase the amount of carbon dioxide in the blood (hypercapnia)

Don’t underestimate patients with COPD, they will usually have an episode of acute dyspnea manifested at rest, an increase in mucus production, or an increase in the general malaise that accompanies the disease.

These patients are already tired so, any worsening dyspnea can cause exhaustion and impending respiratory arrest, quickly!

These patients will often give the EMS professional clues at first sight.

They are often in severe respiratory distress, found sitting upright in a leaning forward in a tripoding position in an unconscious attempt to increase the ease of respirations.

They may also be breathing through pursed lips; the bodies attempt to keep the collapsing alveoli open at the end of respiration.

Asthma

Asthma, also known as “reactive airway disease,” is an allergic condition that results in chronic changes in the lungs.

It also often results in sudden and severe increases in symptoms that are known as “exacerbations.”

Asthma is most common in children and many children outgrow this condition early in life.

Adults with asthma are typically affected for life in varying degrees of severity.

Asthma attacks are episodes that are defined by sudden obstruction of the airways due to spasms of the smooth muscle that makes up the bronchioles. Increased mucus secretion also occurs which further worsens obstruction.

Several other changes also occur.

- Entire areas of the lung can become blocked off due to hardened plugs of mucus

- This sudden blockage results in difficulty getting air into AND out of the lungs

- Reduced airflow to the lungs leads to low oxygen levels and increased carbon dioxide levels

- The body makes the muscles of the chest wall, neck, and abdomen work extra hard in an attempt to drive air into the lungs

Most asthma-related deaths occur outside of the hospital. In the prehospital setting, cardiac arrest in patients with severe asthma has been linked to the following factors:

- Patients tiring out and being unable to keep using muscles of the chest wall to force air past obstructions

- Severe bronchospasm and mucous plugging leading to hypoxia and resulting PEA or ventricular fibrillation

- Tension pneumothorax from air trapping and lung over-expansion

The asthma patient’s mental status is a good indicator of their respiratory efficiency. Lethargy, exhaustion, agitation, and confusion are all serious signs of impending respiratory failure.

An initial history containing OPQRST/SAMPLE questions is crucial as well as, past episode outcomes (i.e., hospital stays, intubation, CPAP).

On auscultation of the asthmatic lungs, a prolonged expiratory phase may be noted.

Wheezing is normally heard from the movement of air through the narrowed airways.

Inspiratory wheezing does not indicate upper airway occlusion.

It suggests that the large and midsized muscular airways are obstructed, indicating a worse obstruction than if only expiratory wheezes are heard.

Inspiratory wheezes also indicate the large airways are filled with mucus.

The severity of wheezing does not correlate with the degree of airway obstruction.

The absence of wheezing may actually indicate a critical airway obstruction; whereas increased wheezing may indicate a positive response to therapy.

A silent chest (i.e., no wheezes or air movement noted) may indicate a severe obstruction to the point of not being able to auscultate any breath sounds.

Other significant signs and symptoms of asthma include:

- Reduced level of consciousness

- Diaphoresis/pallor

- Sternal/intercostal retractions

- 1 or 2-word sentences from dyspnea

- Poor, flabby muscle tone

- Pulse > 130 bpm

- Respirations > 30 bpm

- Pulsus Paradoxus > 20 mmHg

- End-tidal CO2 > 45 mmHg

BPCO, Chronic bronchopneumatic disease: Asthma, Bronchitis, and Emphysema Management

All patients experiencing shortness of breath will receive oxygen.

Much has been said over the years, and much misinformation exists, in reference to hypoxic drive and COPD patients.

The axiom “All patients who need oxygen should receive it in the field” remains both accurate and a standard of care.

- Patients suffering from asthma should be treated quickly and aggressively with bronchodilating medications and oxygen.

- With known COPD history. 4-6 lpm O2 and monitor SpO2. If not for severe dyspnea administer 10 -15 lpm NRB to maintain a SpO2 >90

- EMS should ask the patient or the patient’s family what medications the patient is prescribed so that the patient is not over-medicated or given a medication that his asthma is resisting.

- Begin an IV of normal saline at a KVO rate mainly for medication administration. Fluid bolus is usually not indicated with asthma.

- If the patient is moving an adequate volume of air: Start a handheld nebulizer treatment using albuterol 2.5 mg with 6-10 lpm oxygen.

- If the patient is too tired to hold the nebulizer it can be connected to a non-rebreather mask with 12 -15 lpm oxygen. (check local protocol). (In the event the patient is not able to breathe deep enough to get the medication into the bronchioles then the patient’s respirations should be assisted with a BVM that has a nebulizer connected).

- It is important to note that the paramedic and the patient will have to work together since a breath must be given by the medic at the same time that a breath is taken by the patient.

- It is tempting in such situations to sedate and intubate the patient. If assisting respirations is not successful then Rapid Sequence Intubation (RSI) should be done but, if possible the patient should be allowed to remain conscious.

- Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation (NPPV) is a way to provide a patient airway support without intubation.CPAP and BI-PAP are both forms of NPPV, that are being used to ventilate patients with COPD. NPPV is especially successful in cases of acute asthma. (check local protocol).

- Since the patient is still conscious they are able to exhale with as much force as possible. This allows more of the inhaled medication to get into the lungs with deeper penetration into the lower airway where the medication may be needed most.

- In patients who have been intubated, emptying of the lungs is dependent on the elasticity of the lungs and ribcage.

- In the event that the patient’s level of consciousness becomes decreased then intubation should be performed in order to improve the patient’s tidal volume and to protect the airway from aspiration. An intubated asthma patient should be given slow deep breaths.

- The lungs should be kept inflated longer than normal to give oxygen and medication time to penetrate the mucus. A long expiration time should also be given to allow the lungs to empty. End-tidal monitoring is especially useful because you can see when the patient has stopped exhaling.

- Caution should be used with patients who are intubated. Pneumothorax can occur whenever a PEEP valve is being used or when the patient is being aggressively ventilated. This is a particular concern when the lungs are already hyper-distended and the treatment being given results in more distention then the pleural lining of the lungs can tolerate.

- Keep in mind that “all that wheezes is not asthma”. In a patient with CHF and asthma, wheezing may just as easily be related to CHF as it is asthma.

- In almost all cases the best treatment for the patient is prompt transport to the emergency department. More time spent in the field results in the options running out before you reach definitive care.

- In severe cases where a long transport time is expected air transport should be considered.

Read Also:

Emergency Live Even More…Live: Download The New Free App Of Your Newspaper For IOS And Android

Blind Insertion Airway Devices (BIAD’s)

Oxygen-Ozone Therapy: For Which Pathologies Is It Indicated?

Hyperbaric Oxygen In The Wound Healing Process

Venous Thrombosis: From Symptoms To New Drugs

What Is Intravenous Cannulation (IV)? The 15 Steps Of The Procedure

Nasal Cannula For Oxygen Therapy: What It Is, How It Is Made, When To Use It

Pulmonary Emphysema: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, Tests, Treatment

Extrinsic, Intrinsic, Occupational, Stable Bronchial Asthma: Causes, Symptoms, Treatment