Arrhythmias, when the heart 'stutters': extrasystoles

Extrasystoles are a very common form of arrhythmia and generally not dangerous: only in a small percentage of heart patients may extrasystoles reserve some surprises

Extrasystoles, when the heart ‘stammers’

The impression is that the heart is ‘babbling’, creating an unpleasantness that forces a coughing fit with the intention of bringing the most important muscle in our body back into rhythm.

These are the so-called extrasystoles, a very common and generally non-threatening form of arrhythmia: only in a small percentage of heart patients may extrasystoles reserve some surprises.

The important thing, therefore, is to understand whether this abnormality of the heart rhythm occurs in a heart or in a heart disease context and to act accordingly.

What is an extrasystole?

It is a “premature” heartbeat, which interrupts the normal and complete filling of the heart, between one beat and the next, producing an almost imperceptible pulsation, often described as a “jump in the heart”, followed by a stronger pulse (a “blow” in the centre of the chest), the effect of the “resetting” of the normal heartbeat.

This sequence (“aborted” heartbeat/strong pulse) may occur several times a day and be unnoticed or barely noticeable, but can often be unpleasant.

Are extrasystoles dangerous to the health of the heart?

If the heart muscle is ‘healthy’, both from the ‘structural’ point of view and in terms of the electrical properties of the cell membranes, extrasystoles are unlikely to create serious problems for the patient.

On the contrary, in the presence of heart disease, both supraventricular extrasystoles (originating in the atria and therefore considered ‘innocent’) and ventricular extrasystoles (originating in the ventricles and therefore more feared) could become ‘triggers’, i.e. initiators of more complex arrhythmias.

Such as the more prolonged tachycardias and the ‘notorious’ atrial fibrillation, as regards supraventricular extrasystoles.

Or ventricular tachycardia or the dreaded ventricular fibrillation in the case of ventricular extrasystoles.

The latter, however, have a further peculiarity.

What is it?

The ‘total number’ of ventricular extrasystoles in 24 hours is not considered the most important factor in assessing their severity.

However, when they account for 20-30% of the total daily beats (i.e., there are at least 15,000 to 20,000 ventricular extrasystoles per day), there may be a gradual deterioration of the “pump function” of the heart, such that even a healthy patient may reach the threshold of heart failure.

How are extrasystoles diagnosed and their risk assessed?

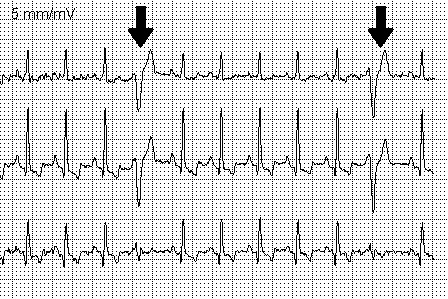

The diagnostic process involves a cardiological examination with an electrocardiogram (ECG).

A careful family history (heart disease or sudden death in the family) and personal history are very important.

In fact, extrasystoles are often facilitated by incorrect behaviour (excessive use of stimulants, such as tea, coffee, alcohol, chocolate, but also a sedentary lifestyle, overweight, gastroesophageal reflux, sleep apnoea, etc.).

An important element of the individual’s medical history is ‘syncope’, i.e. fainting episodes, especially if there is no clear cause.

In the absence of a diagnosis of heart disease – as is the case in most cases – the patient can be reassured and dismissed with some behavioural advice (e.g. reduce the use of stimulants, etc.).

If not, further investigations are carried out.

Which ones?

The most commonly used and well-known test is the dynamic Holter ECG (“Holter ECG”), i.e. the recording of the electrocardiogram for 24 hours.

This test documents the number of extrasystoles in a day and compares it to the total number of heartbeats.

In addition, it is assessed whether extrasystoles prevail during wakefulness or sleep, during physical activity or rest; whether they occur one at a time (isolated) or in sequences of two, three or more beats (repetitive); whether they occur at regular intervals (bigeminism, trigeminism) or not.

Another important factor is their earliness, i.e. the temporal relationship between the extrasystole and the previous beat (which is often in some way at the origin of the extrasystole itself).

Finally, the Holter ECG allows us to appreciate any changes in the appearance of certain components of the electrocardiogram (for example, T waves or the QT interval), which can be correlated with any underlying heart disease and evaluated for possible consequences.

In order to capture all this information, it is necessary for the Holter ECG to provide a “complete” electrocardiographic recording, i.e. “12-lead”, like that of the normal ECG tracing.

Is the Holter ECG sufficient to provide a complete diagnostic picture of extrasystoles?

The Holter ECG provides a purely electrical assessment of the extrasystole phenomenon.

For a morphological and functional assessment of the heart, it is necessary to use other examinations, mostly outpatient and non-invasive.

First of all, the colour Doppler echocardiogram provides a great deal of information.

In selected cases, Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging is now also available, which provides complementary information to that of the echocardiogram.

The cycle ergometer stress test, on the other hand, is the simplest ‘stress test’ for assessing the behaviour of extrasystoles during exercise, under controlled and safe conditions.

Invasive examinations may also sometimes be necessary: for example, coronarography, which is useful in the hypothesis of an ischaemic origin of arrhythmias, and electrophysiological studies, which assess the vulnerability of cardiac tissue to more complex arrhythmias (which – as we have said – the same extrasystoles could trigger) and allow us to ‘map’ the origin of extrasystoles with extreme precision, thanks to leads introduced into the cardiac cavities.

These invasive examinations require a short stay in hospital and patients should always be well informed about the possible risks and the risk/benefit ratio of such tests.

Is the treatment of extrasystoles then limited to a change in lifestyle?

This is often the case, especially in the absence of heart disease.

If, however, the symptoms are disabling for the normal course of daily activities, drug therapy aimed at reducing extrasystoles can be initiated.

The most commonly prescribed drugs are beta-blockers or certain calcium channel blockers.

In selected cases, genuine antiarrhythmic drugs are used, which have a more complex mechanism of action and are the exclusive responsibility of specialists.

In the case of patients with heart disease?

In patients with heart disease, the treatment of extrasystoles coincides with and often complements the treatment of the underlying pathology.

For some patients, whether they have heart disease or not, who are very symptomatic, an attempt at ablation of the extrasystoles may finally be proposed: this is an invasive therapy, which complements the electrophysiological study, aimed at reclaiming the area of tissue from which the extrasystoles originate, by means of cautery which switches off their activity.

For patients with severe heart disease and a poor prognosis, the implantation of an Automatic Cardiac Defibrillator (AICD) should still be considered, because there is no guarantee that drug therapy will completely extinguish extrasystoles and with them the risk of more serious, even fatal, arrhythmias.

Why is it believed that extrasystoles can be caused by gastroesophageal reflux?

A definite cause-and-effect relationship between extrasystoles and gastro-oesophageal reflux has never been fully proven, but it is common knowledge that difficult digestion and gastro-oesophageal reflux can be triggers of extrasystoles.

In particular, in the case of supraventricular extrasystoles, it has been hypothesised that the anatomical contiguity between the oesophagus and the left cardiac atrium may transmit irritation of the oesophageal mucosa, due to acid reflux from the stomach, to the heart, promoting extrasystole.

So, is an antacid enough?

Sometimes… But you should never make a hasty diagnosis.

Even ‘innocent’ supraventricular extrasystoles could be a sign of a not well controlled arterial hypertension, or of an initial pathology of the heart valves.

Therefore, the cardiologist must be extremely careful and scrupulous, even though he or she is aware that – in the vast majority of cases – extrasystoles are and remain a benign symptom, without significant consequences.

Read Also:

Heart Failure: Causes, Symptoms, Tests For Diagnosis And Treatment

Heart Patients And Heat: Cardiologist’s Advice For A Safe Summer

Silent Heart Attack: What Is Silent Myocardial Infarction And What Does It Entail?