Basic life support (BTLS) and advanced life support (ALS) to the trauma patient

Basic trauma life support (BTLS): basic trauma life support (hence the acronym SVT) is a rescue protocol generally used by rescuers and aimed at the first treatment of injured persons who have suffered trauma, i.e. an event caused by a considerable amount of energy acting on the body causing damage

This type of rescue is therefore aimed not only at polytrauma victims who have suffered e.g. road accidents, but also at drowned, electrocuted, burnt or gunshot wounds, since in all these cases the injuries are caused by the dissipation of energy on the body.

SVT and BTLF: Golden hour, speed saves a life

One minute more or less is often the difference between life and death for a patient: this is even truer in the case of patients who have suffered severe trauma: the time between the trauma event and the rescue is of great importance, since obviously the shorter the time interval from the event to the intervention, the greater the chance that the traumatised person will survive or at least suffer the least possible damage.

For this reason, the concept of the golden hour is important, which emphasises that the time between the event and the medical intervention should not be more than 60 minutes, a limit beyond which there is a marked increase in the chances of not saving the patient’s life.

However, the expression ‘golden hour’ does not necessarily refer to an hour, but rather expresses the general concept that: ‘the earlier action is taken, the greater the chance of saving the patient’s life’.

Elements of major trauma dynamics

When a citizen calls the Single Emergency Number, the operator asks him/her some questions about the dynamics of the event, which serve to

- assess the severity of the trauma

- establish a priority code (green, yellow or red);

- send the rescue team as necessary.

There are elements that predict a supposed greater severity of the trauma: these elements are called ‘elements of major dynamics’.

The main elements of major dynamics are

- age of the patient: an age of less than 5 and more than 55 is generally an indication of greater severity;

- violence of the impact: a head-on collision or the ejection of a person from the passenger compartment are, for example, indications of greater severity;

- collision between vehicles of opposite size: bicycle/truck, car/pedestrian, car/motorbike are examples of increased severity;

- persons killed in the same vehicle: this raises the hypothetical level of severity;

- complex extrication (expected extrication time of more than twenty minutes): if the person is trapped e.g. between metal sheets, the hypothetical gravity level is raised;

- fall from heights greater than 3 metres: this raises the hypothetical level of severity;

- type of accident: electrocution trauma, very extensive second or third degree burns, drowning, gunshot wounds, are all accidents that raise the hypothetical level of severity;

- extensive trauma: polytrauma, exposed fractures, amputations, are all injuries that raise the level of severity;

- loss of consciousness: if one or more subjects have loss of consciousness or an inoperable airway and/or cardiac arrest and/or pulmonary arrest, the severity level is raised considerably.

Objectives of the telephone operator

The objectives of the telephone operator will be to

- interpret the description of the incident and of the clinical signs, which are often rather inaccurately presented by the caller, who obviously will not always have a medical background;

- understand the seriousness of the situation as quickly as possible

- send the most appropriate assistance (one ambulance? two ambulances? Send one or more doctors? Also send fire brigade, carabinieri or police?);

- reassure the citizen and explain to him at a distance what he can do while waiting for help.

These objectives are easy to say, but very complex in view of the excitement and emotion of the caller, who is often faced with traumatic incidents or has himself been involved in them and therefore his own description of what happened may be fragmentary and altered (e.g. in the case of concussion, or alcohol or drug use).

SVT and BTLF: primary and secondary injuries

In this type of event, damage can be distinguished into primary and secondary damage:

- primary damage: this is the damage (or damages) that is directly caused by the trauma; for example, in a car accident, the primary damage that a person may suffer may be fractures or amputation of limbs;

- secondary damage: this is the damage that the patient suffers as a result of the trauma; in fact, the energy of the trauma (kinetic, thermal, etc.) also acts on internal organs and can cause more or less serious damage. The most frequent secondary damage may be hypoxia (lack of oxygen), hypotension (lowering of blood pressure due to the onset of a state of shock), hypercapnia (increase of carbon dioxide in the blood) and hypothermia (lowering of body temperature).

SVT and BTLF protocols: the Trauma Survival Chain

In the event of trauma, there is a procedure to coordinate rescue actions, called the trauma survivor chain, which is divided into five main steps

- emergency call: early warning through an emergency number (in Italy it is the Single Emergency Number 112);

- triage carried out to assess the severity of the event and the number of people involved;

- early basic life support;

- early centralisation at Trauma Centre (within the golden hour);

- early advanced life support activation (see last paragraph).

All links in this chain are equally important for a successful intervention.

Rescue team

A team acting on an SVT should consist of at least three people: Team Leader, First Responder and Rescue Driver.

The following diagram is purely ideal, as the crew may vary depending on the organisation, the regional rescue law and the type of emergency.

The team leader is generally the most experienced or senior rescuer and manages and coordinates the operations to be performed during a service. The team leader is also the one who carries out all assessments. In a team in which a 112 nurse or doctor is present, the role of team leader automatically passes to them.

The Rescue Driver, in addition to driving the rescue vehicle, takes care of the safety of the scenario and helps the other rescuers with immobilisation manoeuvres.[2]

The First Responder (also called the manoeuvre leader) stands at the head of the trauma patient and immobilises the head, holding it in a neutral position until the immobilisation on a spinal board is completed. In the event that the patient is wearing a helmet, the first rescuer and a colleague handle the removal, keeping the head as still as possible.

Stay & play or scoop & run

There are two strategies for approaching the patient and they should be chosen according to the characteristics of the patient and the local healthcare situation:

- scoop & run strategy: this strategy should be applied to critically ill patients who would not benefit from on-site intervention, even with Advanced Life Support (ALS), but require immediate hospitalisation and in-patient treatment. Conditions requiring Scoop & Run include penetrating wounds to the trunk (chest, abdomen), limb root and neck, i.e. anatomical sites whose wounds cannot be effectively compressed;

- stay & play strategy: this strategy is indicated for those patients who require stabilisation in situ before being transported (this is the case with massive compressible haemorrhages or more serious than urgent situations).

BLS, trauma life support: the two assessments

Basic life support to the traumatised person starts from the same principles as normal BLS.

BLS to the traumatised person involves two assessments: primary and secondary.

The immediate assessment of the trauma victim’s consciousness is essential; if this is absent, the BLS protocol must be applied immediately.

In the case of an incarcerated casualty, a rapid assessment of Basic Life Functions (ABC) is crucial, and is necessary to direct the rescue team to either a rapid extrication (in case of unconsciousness or impairment of one of the VFs) or a conventional extrication using the KED extrication device.

Primary assessment: the ABCDE rule

After the rapid assessment and an extrication if necessary, the primary assessment is performed, which is divided into five points: A, B, C, D and E.

Airway and Spine Control (airway and cervical spine stabilisation)

The First Responder positions himself at the head stabilising it manually while the Team Leader applies the cervical collar. The team leader assesses the state of consciousness by calling the person and establishing physical contact, e.g. by touching their shoulders; if the state of consciousness is altered it is essential to notify 112 quickly.

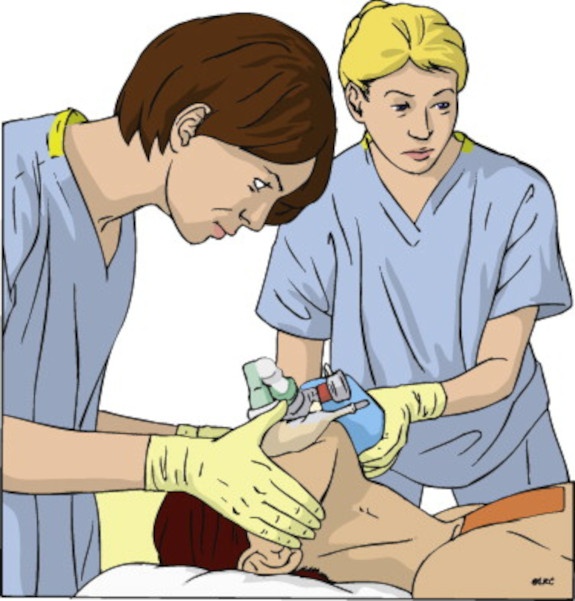

Also at this stage, the team leader uncovers the patient’s chest and checks the airway, placing an oro-pharyngeal cannula if the patient is unconscious.

It is important to always administer oxygen at high flows (12-15 litres/minute) to the casualty, as he/she is always considered to be in hypovolaemic shock.

B – Breathing

If the patient is unconscious, after alerting 112, the team leader proceeds with the GAS (Look, Listen, Feel) manoeuvre, which is used to assess whether the person is breathing.

If there is no breathing, the classic BLS is performed by carrying out two ventilations (possibly by connecting the self-expanding flask to the oxygen cylinder, making it deliver at high flow rates), and then moves on to phase C.

If breathing is present or if the patient is conscious, the mask is positioned, oxygen is administered and the OPACS (Observe, Palpate, Listen, Count, Saturimeter) is performed.

With this manoeuvre, the team leader assesses various parameters of the patient: in fact, he observes and palpates the chest checking that there are no hollows or abnormalities, listens to the breath checking that there are no gurgles or noises, counts the respiratory rate and uses the saturimeter to assess oxygenation in the blood.

C – Circulation

In this phase, it is checked whether the patient has had any massive haemorrhages requiring immediate haemostasis.

If there are no massive haemorrhages, or at least after they have been tamponaded, various parameters regarding circulation, heart rate and skin colour and temperature are assessed.

If the patient in phase B is unconscious and not breathing – after performing two ventilations – we move on to phase C, which consists of checking for the presence of a carotid pulse by placing two fingers on the carotid artery and counting to 10 seconds.

If there is no pulse we move on to cardiopulmonary resuscitation practised in BLS by performing cardiac massage.

If there is a pulse and no breath, breathing is assisted by performing about 12 insufflations per minute with the self-expanding balloon connected to the oxygen cylinder that delivers high flows.

If the carotid pulse is absent the primary assessment stops at this point. The conscious patient is treated differently.

The blood pressure is assessed using a sphygmomanometer and radial pulse: if the latter is absent, the maximum (systolic) blood pressure is less than 80 mmHg.

Since 2008, phases B and C have been merged into a single manoeuvre, so that the verification of the presence of the carotid pulse is simultaneous with that of the breath.

D – Disability

Unlike the initial assessment where the state of consciousness is assessed using the AVPU scale (nurses and doctors use the Glasgow Coma Scale), in this phase the person’s neurological state is assessed.

The rescuer asks the patient simple questions assessing

- memory: he asks if he remembers what happened;

- spatio-temporal orientation: the patient is asked what year it is and whether he knows where he is;

- neurological damage: they assess using the Cincinnati scale.

E – Exposure

In this phase it is assessed whether the patient has suffered more or less severe injuries.

The team leader undresses the patient (cutting clothes if necessary) and makes an assessment from head to toe, checking for any injuries or bleeding.

Protocols call for checking the genitals as well, but this is often not possible either because of the patient’s wishes or because it is easier to ask the patient if he/she feels any pain himself/herself.

The same goes for the part where clothes should be cut off; it may happen that the patient is against this, and sometimes the rescuers themselves decide not to do it if the patient reports no pain, moves his limbs well and ensures that he has not suffered any blows in a certain area of his body.

Following the head-foot check, the patient is covered with a heat cloth to prevent possible hypothermia (in this case, the rise in temperature must be gradual).

At the end of this phase, if the patient has always been conscious, the team leader communicates all the ABCDE parameters to the 112 operations centre, which will tell him what to do and which hospital to transport the patient to. Whenever there are substantial changes in the patient’s parameters, the team leader must notify 112 immediately.

Secondary evaluation

Evaluate:

- dynamics of the event;

- mechanism of the trauma;

- patient history. After completing the primary assessment and alerting Emergency Number of the condition, the operations centre decides whether to have the patient transported to hospital or to send another rescue vehicle, such as an ambulance.

According to PTC protocol, loading onto the spinal column should be done with the spoon stretcher; other literature and stretcher manufacturers, however, state that as little movement as possible should be done and therefore loading onto the spinal column should be done with the Log roll (tie the feet together first), so that the back can also be inspected.

Advanced life support (ALS)

Advanced life support (ALS) is the protocol used by medical and nursing staff as an extension of, not a replacement for, basic life support (BLS).

The purpose of this protocol is the monitoring and stabilisation of the patient, also through the administration of drugs and the implementation of invasive manoeuvres, until arrival at the hospital.

In Italy, this protocol is reserved for doctors and nurses, while in other states, it can also be applied by personnel known as ‘paramedics’, a professional figure absent in Italy.

Read Also:

Emergency Live Even More…Live: Download The New Free App Of Your Newspaper For IOS And Android

ABC, ABCD And ABCDE Rule In Emergency Medicine: What The Rescuer Must Do

Evolution Of Pre-Hospital Emergency Rescue: Scoop And Run Versus Stay And Play

What Should Be In A Paediatric First Aid Kit

Does The Recovery Position In First Aid Actually Work?

Is Applying Or Removing A Cervical Collar Dangerous?

Cervical Collars : 1-Piece Or 2-Piece Device?

Cervical Collar In Trauma Patients In Emergency Medicine: When To Use It, Why It Is Important

KED Extrication Device For Trauma Extraction: What It Is And How To Use It

How Is Triage Carried Out In The Emergency Department? The START And CESIRA Methods