Constrictive pericarditis and exudative constrictive pericarditis

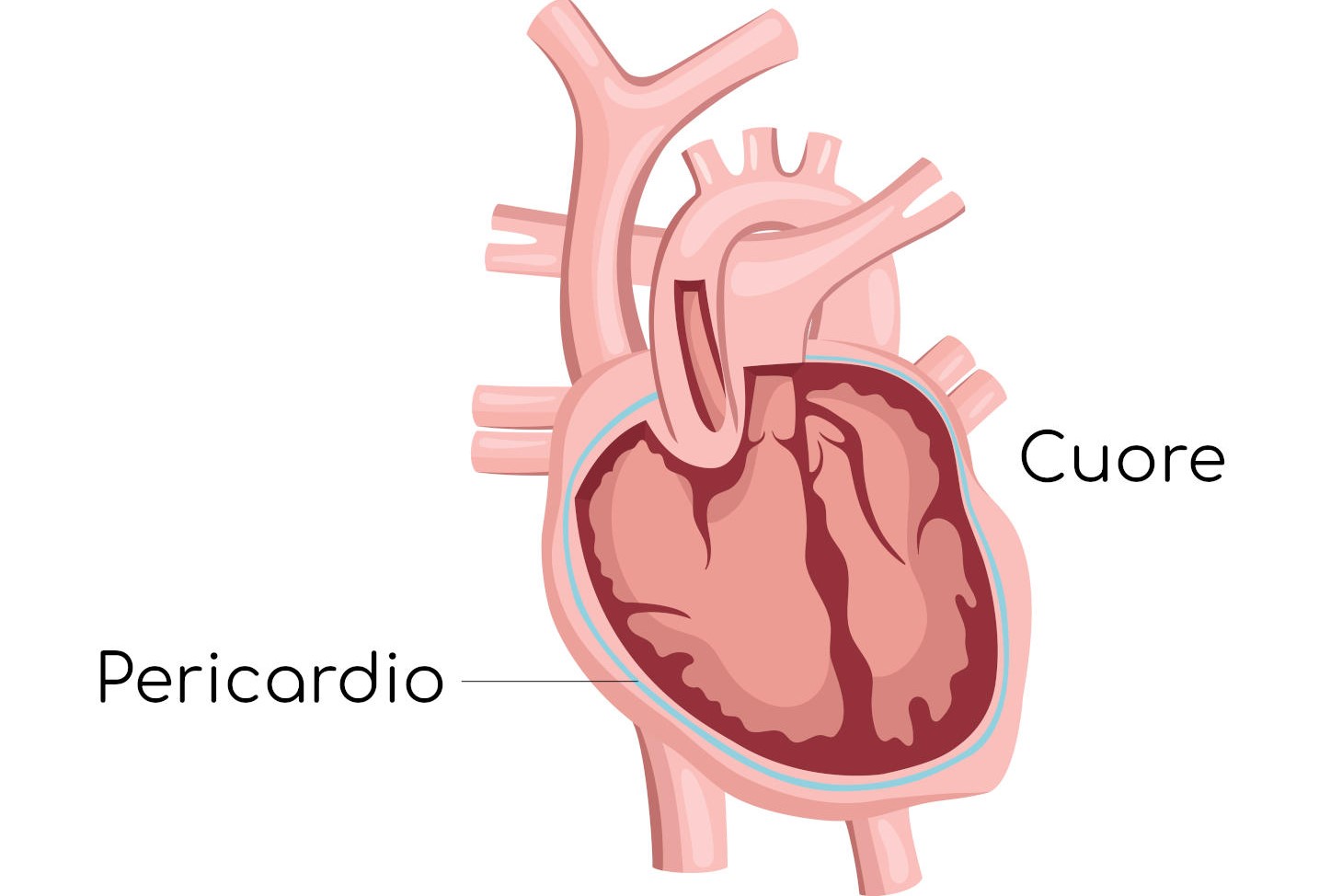

Let’s talk about constrictive pericarditis. The pericardium is a thin membrane that surrounds the heart, consisting of two layers: the fibrous pericardium (the outer layer) and the serous pericardium (the inner layer)

Constrictive pericarditis’ develops from permanent scarring of the pericardium in response to various inflammatory conditions

It is characterised by a thickened, fibrotic (or calcified) pericardium that restricts diastolic filling of the heart.

The pathological process is often diffuse and symmetrical, resulting in elevated and levelled diastolic pressures in all four cardiac chambers.

However, unlike tamponade, in which ventricular filling is impaired throughout diastole, early diastolic filling is not impaired in constrictive pericarditis.

This circumstance leads to rapid early ventricular filling, secondary to increased atrial pressure, followed by a sudden rise and plateau (square root sign) of ventricular pressure during meso- and telediastole as soon as the ventricular volume reaches the limit set by the non-distensible pericardium.

Causes of obstructive pericarditis

The causes of pericardial constriction are similar to those that lead to pericarditis and are infection, radiation exposure, connective tissue disorders and uremia.

In addition, this condition can occur several months or years after heart surgery.

Before the introduction of an effective anti-tuberculosis treatment, mycobacterium tuberculosis was the most common cause.

However, as with pericarditis, most cases of pericardial constriction have no identifiable aetiology and are therefore termed idiopathic.

Symptoms and signs of obstructive pericarditis

Patients with mild to moderate constriction complain of abdominal pain and have swelling of the lower extremities from liver congestion and peripheral oedema.

As the process worsens, decreased cardiac output causes more severe asthenia and dyspnoea, and pulmonary congestion may cause coughing, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnoea (PND) and orthopnoea.

Diagnosis of obstructive pericarditis

On objective examination, the jugular veins are distended and distend paradoxically on inspiration (Kussmaul’s sign), which occurs because negative intrathoracic pressure is not transmitted to the peri-cardium or in the presence of constrictive physiology.

As a result, an increase in venous return cannot be allocated from the right atrium and ventricle, and the jugular veins become further distended.

The increase in central venous pressure is accompanied by prominent negative x- and y-waves.

The negative y-wave, which is absent or diminished in tamponade, is prominent and shortened due to a rapid rise in pressure in mesodiastole.

In constrictive pericarditis the paradoxical pulse is typically not present because inspiration does not result in increased ventricular filling.

Other objective findings include signs of right ventricular decompensation, such as hepatomegaly, ascites and peripheral oedema.

On objective examination, a protodiastolic tone (pericardial stroke) at the left sternal margin just after the aortic component of S2 may be appreciated and corresponds to the cessation of rapid protodiastolic filling.

Chest X-ray examination may show pericardial calcification and pleural effusions

On electrocardiogram (ECG) the QRS voltage may be reduced with non-specific ST segment and T wave abnormalities.

Although many patients maintain sinus rhythm, some develop ectopy or atrial fibrillation.

On echocardiography, the pericardium may appear thickened and immobile.

Abnormalities of the parietal kinetics of the interventricular septum and dilatation of the inferior vena cava are also often found.

Echocolordoppler shows abnormal flow velocity in the pulmonary and hepatic veins and an abnormal pattern of diastolic ventricular filling.

CT and MRI are also used to measure pericardial thickness.

As with echocardiography, MRI can be valuable in detecting the haemodynamic consequences of constrictive pericarditis

In most patients, right heart catheterisation is necessary to make the diagnosis.

Typical findings include increased and equalised atrial and ventricular diastolic pressures.

Elevation of central venous pressure is accompanied by prominent negative x- and y-waves.

The negative y-wave, which is absent or diminished in tamponade, is prominent due to rapid atrial emptying in protodiastole but shortened due to rapid right ventricular pressure rise in mesodiastole.

Both right and left ventricular diastolic pressures show a decrease in protodiastole followed by a rapid rise and plateau in meso- and telediastole, a sign of the square root, as further filling is compromised by the non-distensible pericardium.

In contrast to restrictive cardiomyopathy, right and left ventricular diastolic pressure tracings are almost superimposable and do not change with volume loading or physical activity.

In difficult cases where differentiation from restrictive cardiomyopathy is uncertain, a pericardial or myocardial biopsy may be useful.

Therapy of obstructive pericarditis

Obstructive pericarditis is a progressive disease.

Treating patients with mild constrictive pericarditis by restricting salt intake and administering diuretics can yield excellent results.

Sinus tachycardia is a compensatory mechanism, so the use of drugs that slow the heart rate (beta-blockers or calcium antagonists) requires some caution.

In most symptomatic patients, surgical removal of the pericardium (pericardiectomy) is the treatment of choice.

Patients with constrictive pericarditis secondary to radiation exposure have a relatively worse long-term prognosis.

Pericardial disease with constriction results in the exclusion of an athlete from all competitive sports.

Exudative constrictive pericarditis

Exudative constrictive pericarditis refers to a clinical haemodynamic syndrome in which constriction on the heart by the visceral pericardium occurs in the presence of a tense effusion in the free pericardial space.

It may represent an intermediate stage in the development of constrictive pericarditis.

The causes of exudative constrictive pericarditis are the same as those of constrictive pericarditis.

However, exudative constrictive pericarditis appears more often in radiation-induced pericarditis and is relatively less frequent in post-surgical cases.

Clinical features resemble those of both tamponade and constriction, with signs of right ventricular decompensation more common.

Despite the usefulness of non-invasive tests such as echocardiography, MRI and CT, the diagnosis is usually made following a successfully performed pericardiocentesis.

After fluid drainage and intrapericardial pressure drop to zero, intracardiac pressures remain elevated, with the presence of constrictive physiology.

The ventricular pressure tracing shows a typical square root sign, while the atrial pressure and jugular venous pulse show a prominent negative y-wave.

Consequently, pericardiocentesis does not relieve the patient’s symptoms.

Surgical management by excision of the peri-cardium or visceral and parietal is usually effective.

Read Also:

Emergency Live Even More…Live: Download The New Free App Of Your Newspaper For IOS And Android

Do You Have Episodes Of Sudden Tachycardia? You May Suffer From Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome (WPW)

Knowing Thrombosis To Intervene On The Blood Clot

Inflammations Of The Heart: What Are The Causes Of Pericarditis?

Pericarditis: What Are The Causes Of Pericardial Inflammation?

Pericarditis In Children: Peculiarities And Differences From That Of Adults

‘D’ For Deads, ‘C’ For Cardioversion! – Defibrillation And Fibrillation In Paediatric Patients

Inflammations Of The Heart: What Are The Causes Of Pericarditis?

Do You Have Episodes Of Sudden Tachycardia? You May Suffer From Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome (WPW)

Knowing Thrombosis To Intervene On The Blood Clot

Patient Procedures: What Is External Electrical Cardioversion?

When To Use The Defibrillator? Let’s Discover The Shockable Rhythms