Eye diseases: glaucoma

Glaucoma is a chronic, bilateral disease of the optic nerve characterised by progressive damage to its nerve fibres; the cause is an internal pressure greater than the eye can tolerate

In practice, a transparent liquid (aqueous humour) is contained within the eye, which serves to nourish the cornea and the crystalline lens, carrying away their waste products: it is produced behind the iris, flows forward and is discharged at the corner of the eye.

If there is no balance between the amount of fluid produced and the amount of fluid discharged, the pressure inside the eye increases.

The flow of the aqueous humour can be compared to the flow of water in a sink: if the faucet is too open (excess production) or if the corner of the eye becomes clogged (defect in discharge), the pressure increases.

If this intraocular hypertension lasts for a long time, the nerve fibres of the optic nerve, which serve to transport the visual stimuli collected by the eye to the brain, are damaged.

Therefore, if the disease goes untreated, the risk of losing sight is high.

Types of Glaucoma

Chronic open-angle glaucoma

This is the most common type of glaucoma due to an imbalance in the amount of aqueous humour present, whereby slowly over time a progressive increase in eye pressure sets in.

It occurs predominantly in adulthood and is more frequent in older people.

Over the age of 65, 1 in 50 people have glaucoma.

Glaucoma is an extremely slow-progressing disease: the first damage is detectable after 10 years on average.

The problem is that because the disease is so slow and painless (asymptomatic), one does not realise one has it until the optic nerve is severely damaged.

Narrow-angle glaucoma

This is the least common type of glaucoma in which, due to a malformation of the angle of the eye, the iris can suddenly lean against the cornea, blocking the outflow of the aqueous humour.

Individuals with this predisposition may thus have, without any premonitory symptoms, an ‘acute glaucoma attack’, in which visual disturbances (blurred vision and coloured halos around lights) may be accompanied by severe pain, nausea and vomiting. In these cases, immediate intervention by an ophthalmologist is necessary.

Pseudoexflative Syndrome (PXS)

This is a secondary type of open-angle glaucoma. In this disease, the crystalline lens and other structures desquamate, producing a kind of dandruff, which clogs the channels through which the aqueous humour drains, causing, in 50% of cases, an increase in eye pressure (pseudo-exfoliative glaucoma).

The incidence of pseudo-exfoliative glaucoma is higher in Northern Europe, with values in Sweden of 75% compared to 10% in the USA.

In Italy it has an incidence of 30%.

In half of the cases the disease affects only one eye.

It is a generalised disease: pseudo-exfoliative material is deposited inside the eye, but also in the vessels and internal organs (heart, liver, kidneys), although no damage other than that caused by glaucoma is known.

Although only in 2% of cases there is a narrow angle, in 2-23% the angle is occludable (possibility of acute glaucoma).

For this reason, a provocation test is recommended. Intraocular pressure has greater daily variability than in chronic simple glaucoma, so it is useful to perform a tonometric curve periodically.

How is glaucoma identified?

The presence of glaucoma can be detected by the following parameters:

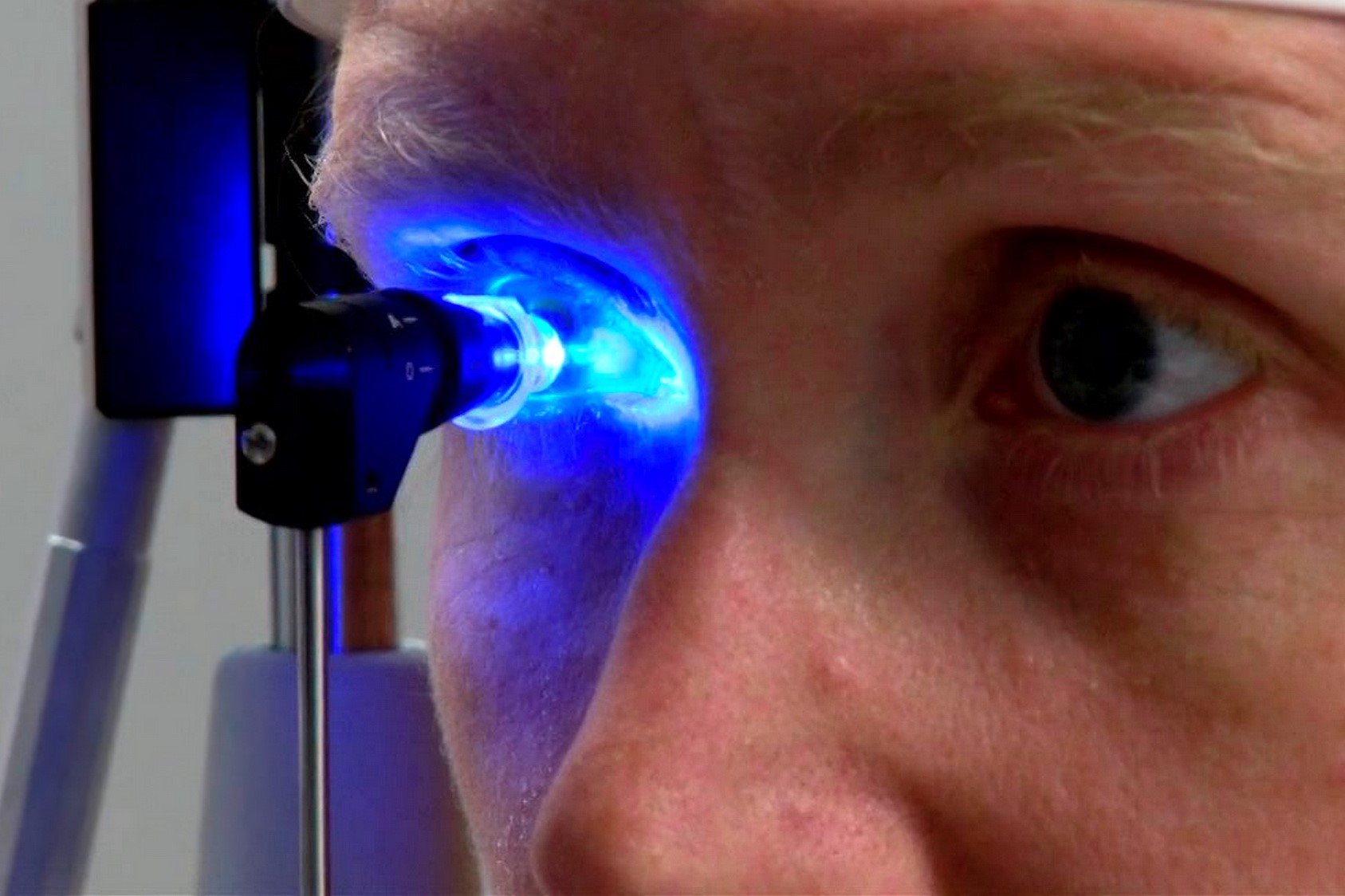

- The measurement of intraocular pressure (Tonometry)

This is a valuable index for detecting a dangerous situation.

The average pressure of white individuals is 16 mm of mercury.

By definition, it is considered high if it is greater than 21 mm Hg.

Therefore, having a pressure of 23 mm carries a 10-fold risk of having glaucoma, at 32 mm the risk is 40 times.

About 40 per cent of glaucoma patients never have high eye pressure (> 22 mm Hg).

This may be due to a structural weakness of the optic nerve or its vascularisation, making it more susceptible to pressure.

This type of glaucoma is called ‘normotensive’; unfortunately, the diagnosis usually occurs at a later stage than in classic chronic glaucoma.

Due to the fact that the intraocular pressure is greater than 22 mm Hg in only 60% of glaucomatous patients, pressure measurement alone is not sufficient as a screening for glaucoma.

- Evaluation of the optic papilla (point where the optic nerve fibres leave the eyeball)

This is observed with ophthalmoscopy or Fundus Examination.

An excavation of the papilla is to be considered suspicious and therefore gives early warning because in some individuals it may indicate glaucoma.

- Assessment of the irido-corneal angle of the eye with Gonoscopy

This is the tangible proof of a real alteration in retinal sensitivity and therefore of damage to the optic nerve.

Glaucoma is an extremely slow-progressing disease: the estimated loss of fibres is 3% per year, which means that the visual field is altered after years of increased pressure in the eye; unfortunately, this is an examination that detects lesions when at least 30% of the optic nerve fibres have already been damaged.

For this reason, alternative damage detection systems are being developed in recent years, which analyse the image of the optic papilla with sophisticated computerised systems (Heidelberg, GDX, SLO).

In order to determine whether glaucoma damage is progressing, it will be necessary to repeat examinations regularly.

What are the risk factors?

- Intraocular pressure values: the incidence of glaucoma increases exponentially with intraocular pressure.

- Familiarity: if parents are affected the risk is 2 times, if siblings are affected 3 times.

- Age: the incidence of glaucoma increases linearly with age. At 60 the risk of glaucoma is double, at 70 it is 2.5 times, over 75 it is 5 times; a positive family history associated with age > 40 carries a 5-fold risk.

- Ocular factors indicating a more susceptible optic nerve: myopia, haemorrhages or atrophy of the retina around the papilla.

- Vasospasm: 48% of normotensive glaucomas suffer from migraine. All diseases that reflect vasomotor instability are to be considered risk factors (peripheral capillary blood flow has been shown to be slower in NTG, with even greater variations after exposure to cold).

- Arterial hypotension (low blood pressure) or other vascular factors (cardiovascular disease, diabetes, increased blood viscosity); those with low blood pressure have a greater deterioration in CV than the normotensive, so especially in normotensive glaucoma, it is useful to inform the internist of the risk of administering a blood pressure-lowering medication.

- Postural alterations: body position influences intraocular pressure; there are subjects with normal intraocular pressure when seated and 37 mm Hg when sitting (e.g. during yoga exercises).

How is glaucoma treated?

In recent years, a huge variety of drugs capable of reducing intraocular pressure (hypotonic) have become available on the market.

Depending on the type, the eye drops must be administered once or several times a day, regularly and continuously.

The aim is to keep the pressure constant over a 24-hour period.

What is the best course of action if a dose is missed? It is necessary to administer the eye drops as soon as possible and then resume at the usual times.

Unfortunately, hypotonic drugs can have side effects and interact with other drugs, so it is important to inform your ophthalmologist of all the medicines you are taking.

It is also necessary to report the onset of any discomfort, so that together we can find an effective and well-tolerated therapy.

What are the side effects of medical therapy?

Ophthalmic drops can cause:

- burning;

- reddening of the eyes;

- blurred vision;

- headaches;

- altered pulse, heartbeat or breathing.

Pills to decrease eye pressure can sometimes cause:

- tingling in the fingers;

- drowsiness;

- bowel irregularities and lack of appetite;

- kidney stones;

- anaemia or ease of bleeding.

Glaucoma: Laser surgery or surgery

If medical therapy is not very effective in reducing eye pressure, laser surgery is used, which is useful in various types of glaucoma.

In classic, chronic, open-angle glaucoma, laser is used to widen the channels through which the aqueous humour flows (trabeculoplasty or ALT). Its efficacy is 80%, but tends to decrease over time.

In angle-closure glaucoma, the laser creates a hole in the iris (iridotomy) to allow the fluid to reach the drainage area.

When surgery is more indicated for glaucoma control, a channel is artificially created through which the aqueous humour can drain from the eye (trabeculectomy or viscocanalostomy).

In 85% of cases a pressure

Successful treatment

The treatment of glaucoma requires a joint effort by the patient and the doctor.

The patient must commit to administering the drops diligently and regularly, while the ophthalmologist must monitor and adjust the therapy as best he can.

It is important never to stop treatment or change medication without first consulting the specialist.

Regular eye check-ups and therapy will continue throughout life.

Read Also:

Emergency Live Even More…Live: Download The New Free App Of Your Newspaper For IOS And Android

Dry Eye Syndrome: Symptoms, Causes And Remedies

Red Eyes: What Can Be The Causes Of Conjunctival Hyperemia?

Autoimmune Diseases: The Sand In The Eyes Of Sjögren’s Syndrome

Corneal Abrasions And Foreign Bodies In The Eye: What To Do? Diagnosis And Treatment

Covid, A ‘Mask’ For The Eyes Thanks To Ozone Gel: An Ophthalmic Gel Under Study

Dry Eyes In Winter: What Causes Dry Eye In This Season?

What Is Aberrometry? Discovering The Aberrations Of The Eye

Raising The Bar For Pediatric Trauma Care: Analysis And Solutions In The US

What Is Ocular Pressure And How Is It Measured?

Opening The Eyes Of The World, CUAMM’s “ForeSeeing Inclusion” Project To Combat Blindness In Uganda

What Is Ocular Myasthenia Gravis And How Is It Treated?

Retinal Detachment: When To Worry About Myodesopias, The ‘Flying Flies’

Retinal Thrombosis: Symptoms, Diagnosis And Treatment Of Retinal Vessel Occlusion