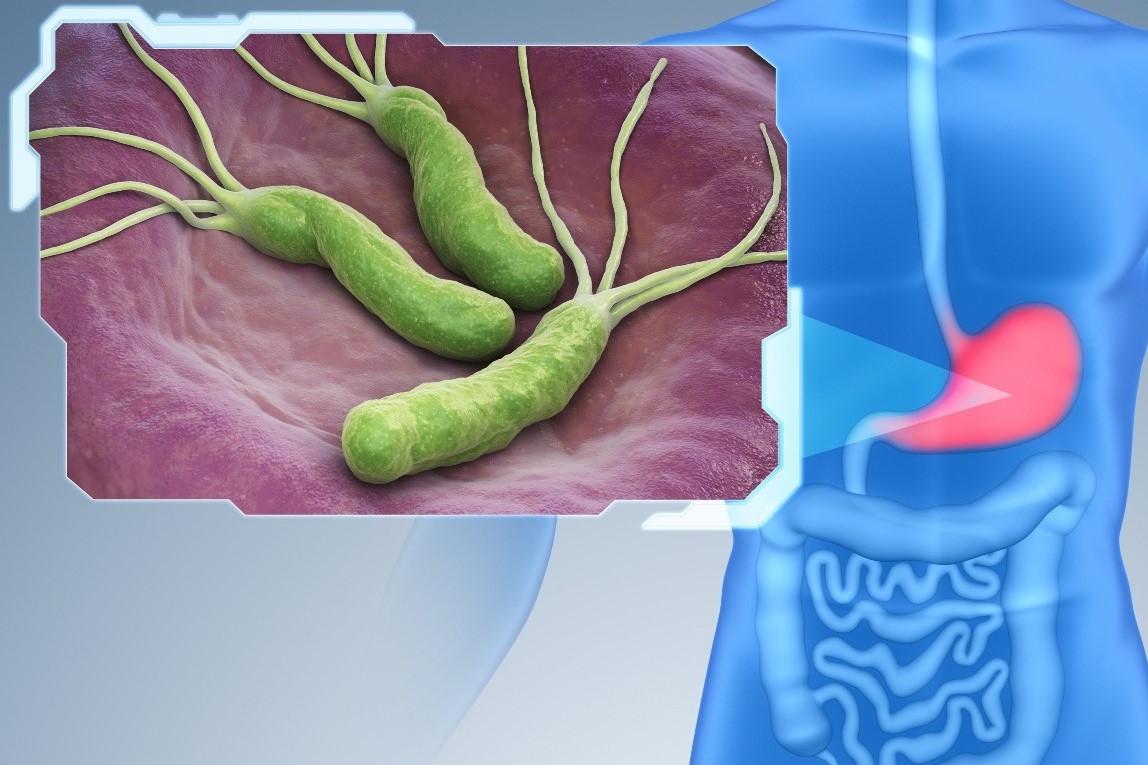

Helicobacter Pylori infection: what are the symptoms?

Helicobacter Pylori is a spiral-shaped Gram-negative bacterium; its main characteristic is that it produces large quantities of urease, an enzyme required for the breakdown of urea with the production of ammonium ions

Helicobacter Pylori only colonises the human gastric mucosa

It is one of the few saprophytic microorganisms observed in the human stomach, whose environment is not normally favourable for bacterial colonisation.

The demonstration of its presence also in faeces and dental plaque suggests an oro-fecal and/or oro-oral transmission.

Its discovery in 1983 in the human stomach changed the approach to peptic diseases.

Indeed, its main role in gastric and duodenal peptic disease has been demonstrated.

Approximately 50% of the world’s population harbours this bacterium in the stomach and its presence appears to increase with age.

Other risk factors are poor hygienic conditions and low socio-economic status.

Helicobacter Pylori infection is one of the most common infections in the world

It is the leading and most frequent cause of peptic ulcers (responsible for about 80% of gastric and duodenal ulcers).

Helicobacter is able to survive the acidic gastro-duodenal environment, penetrate the mucus layer and reach the epithelium thanks to three colonising factors: urease, motility and adhesins.

Urease is an enzyme and its urease activity produces ammonia and bicarbonates.

The latter neutralise the acid in the area where the bacterium, which is mobile, adheres; it therefore reduces the bactericidal activity of the cells and local immunity.

In addition, the bacterium is able to adhere to gastric cells, thus colonising even outside the stomach.

The possibility of movement, thanks to its flagella, is also a resistance factor.

In addition, Helicobacter also manages to survive through antigenic variation and the production of enzymes that destroy antibodies.

Helicobacter Pylori has a wide genetic variability as there are various strains of it, with greater or lesser virulence and aggressiveness

Helicobacter crosses the gastric mucosal barrier and carries out its destructive action through particular enzymes, including urease as mentioned above, lipase, phospholipase A and protease.

In addition, the bacterium produces a protein capable of causing cell death; the presence of antibodies against this protein is a marker of the aggressiveness of the infection.

In fact, the bacterium induces inflammation and produces local cytotoxic substances, distinguishing itself into different types, which can be genetically encoded (such as VacA and CagA, H. Pylori CagA positive being the more virulent strain that causes more severe damage to the mucosa).

What are the symptoms of Helicobacter Pylori?

Most infected persons remain asymptomatic, even in the presence of chronic gastritis.

Chronic gastritis is an acute gastritis whose inflammatory process of the mucosa persists for more than two weeks, often due to the presence of H. Pylori.

The gastritis caused by the infection, by inducing inflammation, stimulating acid hypersecretion and reducing the protective factors of the mucosa, can in turn cause gastric or duodenal ulceration.

In fact, Helicobacter has been shown to play a decisive role in gastric and duodenal ulcers, even taking into account ulcer recurrences, which are generally lower in patients in whom eradication of the bacterium has taken place than in those in whom eradication has not taken place.

The role of Helicobacter Pylori in Gastro-Esophageal Reflux Disease (GERD), on the other hand, although initially considered to be of great significance, was later reconsidered due to the increased frequency of oesophagitis in patients in whom the bacterium had been eradicated anyway.

For this reason, the determination was made not to eradicate the bacterium in MRGE.

However, other reasons, mainly related to the risk of disease occurrence in the presence of H.P. infection, from chronic gastritis to gastric neoplasia (especially gastric adenocarcinoma), subsequently led most experts to make the absolute indication for Helicobacter Pylori eradication even in the case of MRGE alone.

Helicobacter Pylori infection often has no symptoms

Acute infection may cause nausea or vomiting, even briefly, while chronic infection may remain asymptomatic for a long time or present the typical symptoms of gastritis or ulcer: burning, gastric pain, digestive difficulties, dyspepsia, aerogastria, heartburn, belching, lack of appetite, slimming, asthenia, headache, epigastralgia.

The most feared complication is certainly gastric carcinoma, a not-so-rare event, perhaps preceded by a long period of active atrophic chronic gastritis and mucosal metaplasia with the various types of progressive dysplasia (mild, moderate, severe) associated with it.

Chronic gastritis therefore deserves special care and attention, sometimes monitoring by means of endoscopy and the correct biopsy samples for a precise histological examination, also for the necessary staging for the most suitable therapy.

In patients who are carriers of this bacterium, the risk of developing this tumour is much higher, although it has a pathogenesis due to various factors.

Another complication is MALT lymphoma, whereby granulocytes and lymphocytes infiltrate the epithelial layer and organise themselves into lymphoid follicles.

This association between Helicobacter and MALT lymphoma has also been confirmed by epidemiological studies and the regression of the lymphoma itself after eradication of the bacterium.

Then there are other serious and fearsome complications such as digestive haemorrhage and perforation of the gastric or duodenal ulcer, stenosis, acute pancreatitis; all dangerous, sometimes dramatic events that always require urgent medical and surgical intervention.

But normally, gastric and duodenal pathology is remedied, and often resolved and cured, by careful and accurate medical treatment, especially thanks to prompt diagnosis and wise and correct supervision by the treating physician.

Helicobacter Pylori: what tests to do?

A diagnosis of Helicobacter Pylori infection can be made by invasive or non-invasive methods.

One of the invasive methods is to take gastric mucosa during an endoscopic examination, to have it analysed by urease test, histological examination, plate culture or PCR.

As far as non-invasive tests are concerned, one is the Urea Breath Test, performed by orally administering isotope-labelled urea and measuring its concentration in exhaled and specially sampled air.

The other equally reliable and easier non-invasive test is the search for faecal antigen (in faeces) of H. Pylori.

The search for antibodies, on the other hand, can be carried out by analysing blood, saliva, faeces and urine, but it is only able to verify that an HP infection has occurred (or has not occurred), without, however, indicating whether the infection is (is not) still present.

Read Also:

Emergency Live Even More…Live: Download The New Free App Of Your Newspaper For IOS And Android

Helicobacter Pylori: How To Recognise And Treat It

Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS): A Benign Condition To Keep Under Control

Gastroesophageal Reflux: Causes, Symptoms, Tests For Diagnosis And Treatment

Ulcerative Colitis: Phase III Study Shows Efficacy Of Investigational Drug Ozanimod

Peptic Ulcer, Often Caused By Helicobacter Pylori

Helicobacter Pylori Infection: What Causes It, How To Recognise It And Treatment