Ischaemic heart disease: chronic, definition, symptoms, consequences

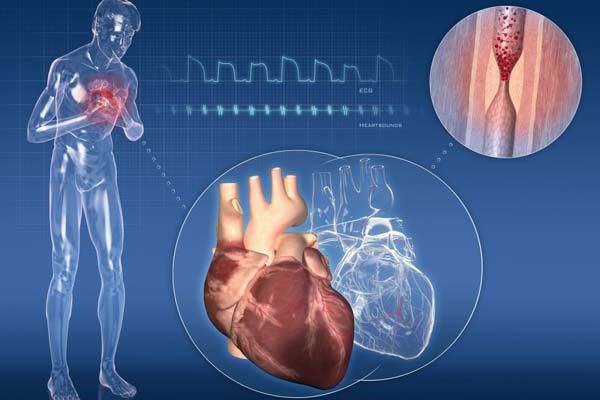

The term ‘ischaemic heart disease’, also called ‘myocardial ischaemia’, refers to a diverse group of pathologies that have in common an insufficient blood supply to the myocardium, i.e. the heart muscle

The most frequent cause is atherosclerosis, characterised by the presence of plaques with a high cholesterol content (atheromas), but ischaemic heart disease can occur in any pathology or condition capable of totally or partially obstructing, chronically or acutely, the flow of blood within the coronary arteries, those that supply the myocardium.

Ischaemic heart disease presents different clinical manifestations such as stable and unstable angina pectoris and myocardial infarction.

How does ischaemia occur?

The activity of the heart is characterised by a balance between the oxygen demand of the heart muscle and blood flow.

Indeed, the heart is an organ that uses large amounts of oxygen for its metabolism and, as we know, continuous cardiac activity is necessary for our survival.

In the presence of pathologies or conditions that alter this balance, an acute or chronic, permanent or transient reduction in the supply of oxygen (hypoxia or anoxia) and other nutrients contained in the blood can occur, which in turn can also irreversibly damage the heart muscle, reducing its functionality (heart failure).

Sudden obstruction of the coronary arteries can lead to myocardial infarction with a high risk of circulatory arrest and death of the patient if the coronary circulation is not quickly restored.

What are the causes of ischaemic heart disease?

A distinction is made between causes of ischaemic heart disease and predisposing factors, better known as cardiovascular risk factors.

The most frequent causes of ischaemic heart disease are:

- Atherosclerosis, a disease involving the walls of blood vessels through the formation of plaques with a lipid or fibrous content, which evolve towards the progressive reduction of the lumen or towards ulceration and the abrupt formation of a clot overlying the point of injury. Atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries is the most frequent cause of angina and myocardial infarction.

- Coronary artery spasms, a relatively uncommon condition that leads to a sudden and temporary contraction (spasm) of the muscles of the artery wall, with reduced or obstructed blood flow.

What are the risk factors for ischaemic heart disease?

The cardiovascular risk factors of myocardial ischaemia are:

- obesity;

- cigarette smoking;

- hypercholesterolaemia or increased blood cholesterol levels, which proportionally raises the risk of atherosclerosis;

- hypertension: high blood pressure can have various causes and affects a large proportion of the population over the age of 50. It is associated with an increased likelihood of developing atherosclerosis and its complications;

- diabetes, which together with hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia makes up the metabolic syndrome, a high-risk picture of cardiac ischemia;

- stress;

- sedentary lifestyle;

- genetic predisposition.

What are the symptoms of ischaemic heart disease?

- sweating;

- shortness of breath;

- fainting;

- nausea and vomiting;

- chest pain (angina pectoris or anginal pain), with pressure and pain in the chest, which may radiate to the neck and jaw. It may also occur in the left arm or in the pit of the stomach, sometimes blending with symptoms similar to a trivial abdominal heaviness.

How to prevent ischaemic heart disease?

Prevention is the most important weapon against ischaemic heart disease.

It is based on a healthy lifestyle, which is the same as the one that must be followed by anyone suffering from heart problems.

First of all, it is necessary to avoid smoking and follow a diet low in fat and rich in fruit, vegetables and whole grains.

Occasions of psychophysical stress should be limited or minimised and regular physical activity, appropriate to the patient, should be preferred.

All ‘correctable’ cardiovascular risk factors should be corrected.

Diagnosis of ischaemic heart disease

The diagnosis of ischaemic heart disease requires instrumental examinations that include:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG): records the electrical activity of the heart and allows the detection of abnormalities suggestive of myocardial ischaemia. The Holter is the prolonged 24-hour monitoring of the ECG: in the case of suspected angina, it allows the electrocardiogram to be recorded in everyday life and especially in those contexts in which the patient reports symptoms.

- The stress test: the examination consists of recording an electrocardiogram while the patient performs physical exercise, generally walking on a treadmill or pedalling on an exercise bike. The test is conducted according to predefined protocols, aimed at assessing the functional reserve of the coronary circulation. It is interrupted at the onset of symptoms, ECG changes or elevated blood pressure or once the maximum activity for that patient has been reached in the absence of signs and symptoms indicative of ischaemia.

- Myocardial scintigraphy: this is a method used to assess exercise ischaemia in patients whose electrocardiogram alone would not be adequately interpretable. Also in this case, the patient can perform the examination on an exercise bike or treadmill. Electrocardiographic monitoring is accompanied by the intravenous administration of a radioactive tracer that is localised in the heart tissue if the blood supply to the heart is regular. The radioactive tracer emits a signal that can be detected by a special device, the gamma camera. By administering the radiotracer under resting conditions and at the peak of activity, it is possible to assess whether there is a lack of signal in the latter condition, which is a sign that the patient is suffering from exercise ischaemia. The examination allows not only to diagnose the presence of ischaemia but also to provide more accurate information on its location and extent. The same examination can be performed by producing the hypothetical ischaemia with an ad hoc drug and not with actual exercise.

- Echocardiogram: this is an imaging test that visualises the structures of the heart and the functioning of its moving parts. The device dispenses an ultrasound beam to the chest, through a probe resting on its surface, and processes the reflected ultrasounds that return to the same probe after interacting differently with the various components of the heart structure (myocardium, valves, cavities). Real-time images can also be collected during an exercise test, in which case they provide valuable information on the heart’s ability to contract correctly during physical activity. Similarly to scintigraphy, the echocardiogram can also be recorded after the patient has been administered a drug that can trigger possible ischaemia (ECO-stress), allowing its diagnosis and assessment of its extent and location.

- Coronography or coronary angiography: this is the examination that makes it possible to visualise the coronary arteries by injecting radiopaque contrast medium into them. The examination is performed in a special radiology room, in which all necessary sterility measures are observed. The injection of contrast into the coronary arteries involves the selective catheterisation of an artery and the advancement of a catheter to the origin of the explored vessels.

- CT heart scan or computed tomography (CT): is a diagnostic imaging examination to assess the presence of calcifications due to atherosclerotic plaques in the coronary vessels, an indirect indicator of a high risk of major coronary artery disease. With current equipment, by also administering intravenous contrast medium, it is possible to reconstruct the coronary lumen and obtain information on any critical narrowing.

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Imaging (NMR): produces detailed images of the structure of the heart and blood vessels by recording a signal emitted by cells subjected to an intense magnetic field. It makes it possible to assess the morphology of heart structures, cardiac function and any changes in wall motion secondary to pharmacologically induced ischaemia (cardiac stress MRI).

Treatments of ischaemic heart disease

The treatment of ischaemic heart disease is aimed at restoring direct blood flow to the heart muscle.

This can be achieved with specific drugs or with coronary revascularisation surgery.

Pharmacological treatment must be proposed by the cardiologist in collaboration with the treating physician and may include, depending on the patient’s risk profile or the severity of the clinical signs:

- Nitrates (nitroglycerin): this is a category of drugs used to promote vasodilation of the coronary arteries, thus allowing increased blood flow to the heart.

- Aspirin: scientific studies have established that aspirin reduces the likelihood of a heart attack. In fact, the anti-platelet action of this drug prevents the formation of thrombi. The same action is also carried out by other anti-platelet drugs (ticlopidine, clopidogrel, prasugrel and ticagrelor), which can be administered as an alternative or in combination with aspirin itself, depending on the different clinical conditions.

- Beta-blockers: these slow down the heartbeat and lower blood pressure, thus helping to reduce the work of the heart and thus also its need for oxygen.

- Statins: drugs to control cholesterol that limit its production and accumulation on artery walls, slowing the development or progression of atherosclerosis.

- Calcium channel blockers: these have a vasodilating action on the coronary arteries, increasing blood flow to the heart.

In the presence of certain forms of ischaemic heart disease, interventional therapy may be necessary, which includes several options:

- Percutaneous coronary angioplasty, an operation that involves inserting a small balloon usually associated with a metal mesh structure (stent) into the lumen of the coronary artery during angiography, which is inflated and expanded at the narrowing of the artery. This procedure improves blood flow downstream, reducing or eliminating symptoms and ischaemia.

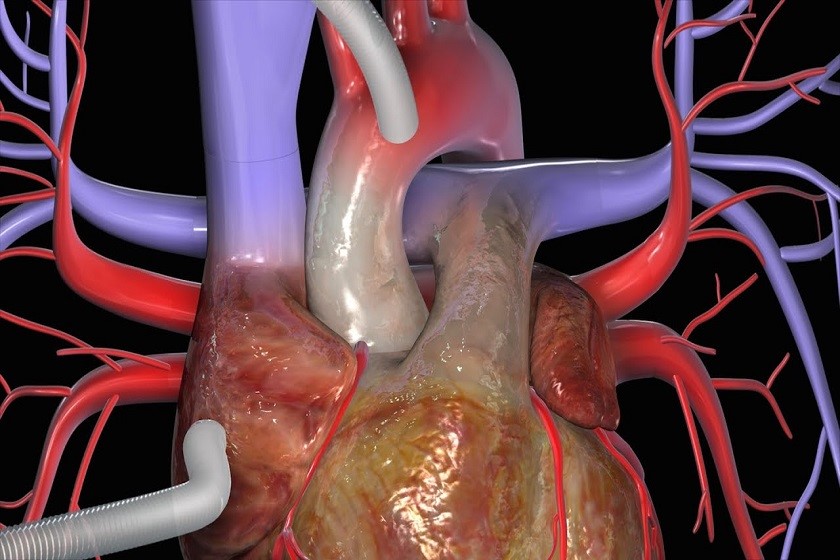

- Coronary artery bypass, a surgical procedure that involves packing vascular conduits (of venous or arterial origin) that can ‘bypass’ the point of narrowing of the coronary artery, thus making the upstream portion communicate directly with the downstream portion of the stenosis. The procedure is performed using various operating techniques, with the patient under general anaesthesia and in many circumstances with the support of extracorporeal circulation.

Read Also:

Emergency Live Even More…Live: Download The New Free App Of Your Newspaper For IOS And Android

Defibrillator: What It Is, How It Works, Price, Voltage, Manual And External

The Patient’s ECG: How To Read An Electrocardiogram In A Simple Way

Signs And Symptoms Of Sudden Cardiac Arrest: How To Tell If Someone Needs CPR

Inflammations Of The Heart: Myocarditis, Infective Endocarditis And Pericarditis

Quickly Finding – And Treating – The Cause Of A Stroke May Prevent More: New Guidelines

Atrial Fibrillation: Symptoms To Watch Out For

Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome: What It Is And How To Treat It

Do You Have Episodes Of Sudden Tachycardia? You May Suffer From Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome (WPW)

Transient Tachypnoea Of The Newborn: Overview Of Neonatal Wet Lung Syndrome

Tachycardia: Is There A Risk Of Arrhythmia? What Differences Exist Between The Two?

Bacterial Endocarditis: Prophylaxis In Children And Adults

Erectile Dysfunction And Cardiovascular Problems: What Is The Link?

Ischaemic Heart Disease: What It Is, How To Prevent It And How To Treat It