Leukemia, an overview

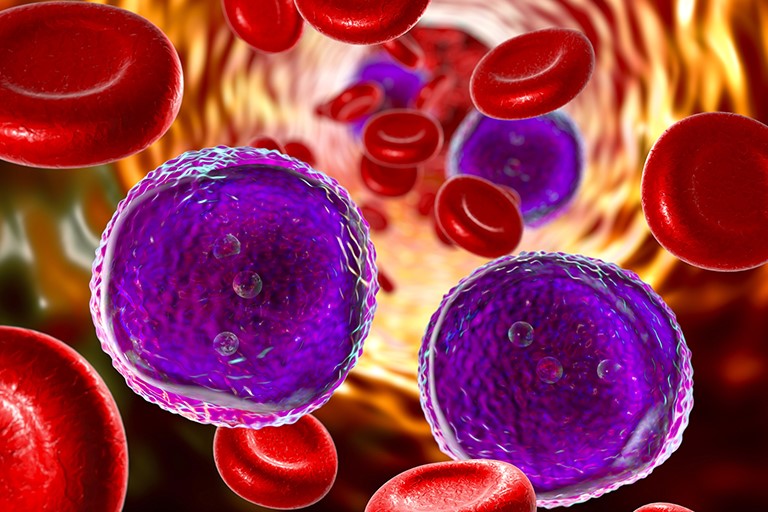

Leukemia is a blood cancer that originates from the uncontrolled proliferation of the cells that compose it

It frequently affects stem cells, i.e. immature cells that, by differentiating, generate white blood cells, red blood cells and platelets

Blood stem cells are located in the bone marrow of flat bones (pelvis, skull, sternum, ribs, vertebrae and scapulae) and long bones (femur and humerus).

Stem cells can differentiate into two different common progenitors: myeloid or lymphoid

Physiologically, myeloid lineage cells create white blood cells (except lymphocytes), red blood cells and platelets, while lymphoid lineage cells transform into lymphocytes.

In some cases it may happen that a stem cell interrupts the maturation process earlier and begins to replicate uncontrollably.

When this happens, copies of the original cell invade the blood, lymph nodes, spleen and liver, resulting in leukaemia.

Leukemia: what is it?

Leukemia is a tumor (neoplasm) that affects blood cells, affecting the body’s hematopoietic tissues, in particular the bone marrow and the lymphatic system.

The term leukemia derives from the union of two Greek words: “leukos”, which means “white” and “aima”, which means “blood”.

“White blood” indicates the characteristic of the majority of leukemias that cause an alteration of leukocytes (white blood cells).

Depending on the type of cells involved and the clinical characteristics, leukemias can be classified as myeloid, lymphoid, acute or chronic.

Exactly identifying the cell from which leukemia originates is essential for setting up a correct therapy and for establishing the prognosis.

Leukemia: classification and types

There are various types of leukemia, classified according to the type of cells that are involved in the tumor process, but also to the course of the disease, the symptoms and the maturation reached by the leukemia cells.

If we take into consideration the clinical trend we find a subdivision into acute leukemia, which usually has a severe prognosis and a rapid course, and chronic leukemia, in which the course is progressive and slow, controllable through drug therapy.

Another distinction can be made by taking into consideration the cells from which the tumor originates.

When the disease affects lymphocytes or cells of the lymphoid lineage, it is called lymphoid or lymphatic leukemia.

If the malignant mutation involves erythrocytes, other leukocytes or platelets, it is in the presence of myeloid leukemia.

There are therefore four main types of leukemia: acute lymphocytic (or lymphoblastic), acute myeloid, chronic lymphocytic, and chronic myeloid.

Acute leukemia

Acute leukemia is a disease that progresses rapidly and symptoms appear early.

Immature cells accumulate in peripheral blood and bone marrow.

The latter is no longer able to produce the other leukocytes, platelets and erythrocytes.

Patients with acute leukemia bleed, are susceptible to infection, develop anemia, and organ infiltration.

Acute leukemia can be myeloid or lymphoblastic.

Acute myeloid leukemia (or AML): Leukemia cells derive from myeloid cell lines and expand in the bone marrow, causing an alteration in the proliferation of normal hematopoietic cells. The result is impaired production of red blood cells (anemia), granulocytes (neutropenia), and platelets (thrombocytopenia). The blasts invade the peripheral blood, reaching the organs.

Acute lymphoid leukemia (or lymphoblastic – ALL): is characterized by a clonal neoplastic disorder with high aggressiveness, which originates from lymphopoietic precursors in the lymph nodes, bone marrow and thymus. We speak of lymphoblastic when the affected cell is poorly differentiated. 80% of acute lymphoblastic leukemias are proliferations of the B chain, 20% derive from the involvement of the T chain precursors.

Chronic leukemia

Chronic leukemia has a slow and relatively stable course over time, unlike that of the acute form.

The pathology is characterized by the progressive accumulation of mature and partly still functional cells in the peripheral blood and bone marrow.

Proliferation in the chronic forms is much less rapid, but becomes more aggressive over time, leading to a progressive increase of neoplastic clones in the bloodstream and worsening of symptoms.

The majority of patients with chronic leukemia are asymptomatic, in other cases the disease causes fever, weight loss, frequent infections, general malaise, thrombosis, lymphadenopathy and thrombosis.

Chronic leukemia can be myeloid or lymphoblastic

Chronic myeloid leukemia (or CML): originates from the transformation of the pluripotent stem cell, which however continues to have the ability to differentiate. Chronic myeloid leukemia is characterized by the proliferation and accumulation of mature granulocyte cells in the bone marrow area. The disorder usually develops and progresses slowly, over years or months. It is the rarest type of leukemia and mostly affects adults.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (or CLL): This is a monoclonal proliferation of small lymphocytes (B) that circulate in the bone marrow, peripheral blood, spleen, and liver. This form of leukemia is the one with the highest incidence in Western countries and mainly affects people over the age of 50.

Leukemia: symptoms

The symptoms of leukemia are related to the type.

Chronic leukemia, for example, often has no symptoms, particularly in the early stages because leukemia cells interfere with other cells to a limited extent.

In acute leukemia, on the other hand, symptoms begin early and worsen rapidly.

Different symptoms can occur depending on the location of the leukemia cells.

For example, headache, tiredness, night sweats, fever, fatigue, joint and bone pain, looking pale, weight loss, enlarged lymph nodes or spleen, bleeding tendency and developing infections.

In some cases leukemia cells can reach the nervous system or organs such as the stomach, lungs, kidneys and intestines, causing malfunctions of the affected organs.

Leukemia: causes and prevention

The causes of leukemia are still being studied today and have not been identified with certainty.

For this reason it is not possible to indicate valid prevention strategies.

How is leukemia diagnosed?

During the medical examination, any increase in the size of the liver, spleen or lymph nodes will be evaluated, as well as the presence of suggestive signs such as paleness or bleeding.

Useful information can derive from blood tests, specifically from the blood count and from indicators of liver and kidney function.

Among the most important signs of leukemia there is, in fact, an altered number of red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets compared to the norm.

Usually, in addition to blood sampling, a “smear” is carried out which allows the cells to be observed under a microscope

This test is very useful for diagnosing the disease, as cancer cells have a different appearance than normal ones.

A bone biopsy and, usually, lumbar puncture are also required for a complete diagnosis.

The bone biopsy involves taking the bone marrow which will then be analyzed under a microscope to evaluate the presence of leukemia cells.

Spine puncture is characterized by the withdrawal of cerebrospinal fluid, which is found in the spaces around the brain and spinal cord.

The aspiration takes place with a needle that is inserted between two lumbar vertebrae.

In this way it is possible to evaluate whether the disease has reached the nervous system.

In addition to these checks, it is advisable to carry out ultrasound, CT and radiography to evaluate any organic involvement of the pathology.

Leukemia: treatment and therapies

Treatment of leukemia is related to the stage of the disease and whether it is chronic or acute.

The age of the patient and the moment in which the diagnosis is made also influence the possibility of treatment.

The treatment of leukemia makes use of the combination of different therapies.

In most cases, chemotherapy is used with the administration of one or more drugs intravenously or by mouth.

Among the most modern therapies are those that stimulate the patient’s immune system to recognize and destroy leukemia cells.

Other approaches include the use of interferon, which slows down the proliferation of cancer cells, and, more recently, the use of monoclonal antibodies that target cancer cells, facilitating their destruction by the immune system.

An effective cure is represented by the transplantation of hematopoietic stem cells which allows the diseased cells, eliminated with high doses of radiotherapy or chemotherapy, to be replaced with healthy ones from a compatible donor.

Usually the donor is a family member, but it can also be a stranger.

This approach allows, in some cases, to permanently cure the pathology, especially in younger patients and in those who no longer respond to other treatments.

Leukemia: evolution of the disease

The stage of leukemia is linked to various factors and each form of the disease is classified with specific criteria and parameters.

Some leukemias have a non-aggressive evolution, others, on the other hand, show very evident and disabling symptoms early.

Read Also

Emergency Live Even More…Live: Download The New Free App Of Your Newspaper For IOS And Android

Leukaemia: Symptoms, Causes And Treatment

What Is Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia?

Leukaemia: The Types, Symptoms And Most Innovative Treatments

Lymphoma: 10 Alarm Bells Not To Be Underestimated

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: Symptoms, Diagnosis And Treatment Of A Heterogeneous Group Of Tumours

CAR-T: An Innovative Therapy For Lymphomas

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia: Long-Term Outcomes Described For Childhood ALL Survivors

Colour Changes In The Urine: When To Consult A Doctor

Why Are There Leukocytes In My Urine?

Acute Lymphocytic Leukaemia: What Is It?

Rectal Cancer: The Treatment Pathway

Testicular Cancer And Prevention: The Importance Of Self-Examination

Testicular Cancer: What Are The Alarm Bells?

The Reasons For Prostate Cancer

Bladder Cancer: Symptoms And Risk Factors

Breast Cancer: Everything You Need To Know

Rectosigmoidoscopy And Colonoscopy: What They Are And When They Are Performed

Bone Scintigraphy: How It Is Performed

Fusion Prostate Biopsy: How The Examination Is Performed

CT (Computed Axial Tomography): What It Is Used For

What Is An ECG And When To Do An Electrocardiogram

Positron Emission Tomography (PET): What It Is, How It Works And What It Is Used For

Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT): What It Is And When To Perform It

Instrumental Examinations: What Is The Colour Doppler Echocardiogram?

Coronarography, What Is This Examination?

CT, MRI And PET Scans: What Are They For?

MRI, Magnetic Resonance Imaging Of The Heart: What Is It And Why Is It Important?

Urethrocistoscopy: What It Is And How Transurethral Cystoscopy Is Performed

What Is Echocolordoppler Of The Supra-Aortic Trunks (Carotids)?

Surgery: Neuronavigation And Monitoring Of Brain Function

Robotic Surgery: Benefits And Risks

Refractive Surgery: What Is It For, How Is It Performed And What To Do?

Anorectal Manometry: What It Is Used For And How The Test Is Performed