Treatment of high blood pressure

In the fight against cardiovascular diseases, the control of high blood pressure is the one that is yielding the best results in terms of cost-effectiveness

Indeed, large pharmacological intervention studies have shown that a reduction of just 10% in blood pressure led to a 40% reduction in mortality from cerebrovascular accidents and a 16-20% reduction in mortality from coronary accidents.

This result, considered by many to be modest, is, however, good when compared with the 40% reduction in coronary mortality achieved with statins, but with more than double the reduction in cholesterolaemia.

Pharmacological research has made a large number of drugs available to the physician with the basic requirements for satisfactory use in the treatment of high blood pressure.

They are characterised by various properties: mechanism of action, side effects, ancillary properties….

The latter, in particular, are those pharmacodynamic characteristics that are specific to certain categories of antihypertensive drugs and not to others, and which, separated from their action on blood pressure, make them particularly useful in the treatment of hypertension associated with other diseases or with organ damage secondary to hypertension.

- antiarrhythmic activity

- antianginal activity

- regression of left ventricular hypertrophy

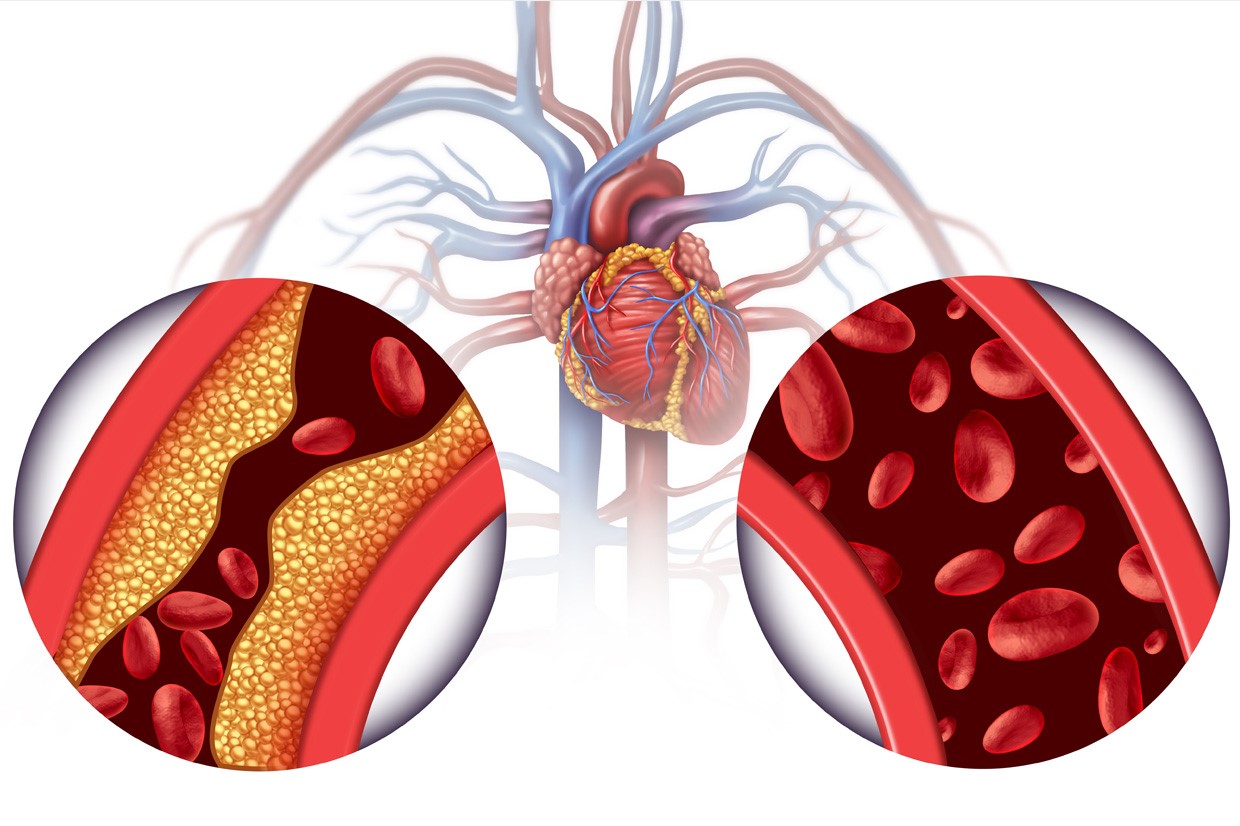

- regression or slowing of the natural history of atherosclerosis

- hypolipidemic activity

- antihemorrhagic activity

- prevention of nephropathy

- efficacy in prostatism

The main tasks of the physician with regard to the hypertensive patient are to document the existence of hypertension and define its severity, to search for related organ damage, and to identify associated pathologies that require therapeutic measures that may interfere with antihypertensive drugs or condition the choice of antihypertensive.

With the exception of chemotherapeutics, antihypertensives are nowadays perhaps the richest category of drugs available to the physician

This is an undoubted advantage over the limited availability in the past, even in the recent past, but it can lead to the risk of total disorientation when making a choice.

This is why it is appropriate to add a few suggestions regarding the criteria to be followed in order to set up a rational and appropriate treatment to bring blood pressure values back to normal or as close to normal as possible.

The first criterion must be based on the degree of hypertension, whether mild, moderate or severe, which, although it has a purely indicative value, is very useful from a clinical-therapeutic point of view.

In the patient with mild hypertension, a sufficiently prolonged period of controlled clinical observation, up to 4-5 months, is in fact advisable before starting therapy, as the blood pressure may return to normal values spontaneously or with simple hygienic-dietetic measures.

Furthermore, in mild hypertension it is advisable to start with ‘light’ drug therapy, as monotherapy, since blood pressure control is often easy and the risk of complications is projected far into the future and is in any case low.

In the case of moderate or severe hypertension, on the other hand, there is no longer any doubt as to the appropriateness of immediate pharmacological treatment.

In this case, the patient will be started on therapy, which must be undertaken gradually and continuously.

This is most often carried out in steps (‘step up’): starting with one drug, to be associated, in the event of an unsatisfactory therapeutic response, with a second drug and then a third and so on until the hypertension is controlled.

Sometimes not being able to foresee the most effective and best tolerated drug, one can already start with a combination of two antihypertensives, to try to discontinue one of them after normalisation of the tension values, to identify the one responsible for the good response (‘step down’). Finally, one can try one type of antihypertensive, to be modified, in the event of an unsatisfactory response, by another with different pharmacodynamic characteristics (‘side stepping’).

The first way of conducting therapy (‘step up’) is the one recommended many years ago by the American Joint National Committee and is still widely followed.

The second (‘step down’) is used when it is necessary to obtain good pressure control quickly, but then want to lighten the treatment schedule.

The third (‘side stepping’) requires a long observation period and should only be followed when there is no hurry to normalise blood pressure values, since for many antihypertensives the maximum therapeutic response does not appear until a few weeks later.

Another useful criterion for the purposes of the therapeutic approach is that which is based on the presence or absence of organ damage, that is, on the consequences of hypertension

It is clear that the treatment of hypertension that has already led to heart failure, cerebrovascular accidents or renal failure poses much more difficult problems than hypertension without obvious complications and requires considerable effort on the part of the doctor.

A third criterion is that of the possible presence of concomitant pathologies on which some antihypertensive drugs can negatively interfere or whose treatment can negatively interact with that of hypertension.

This is the case of migraine hypertension in which the use of non-cardioselective beta-blockers can control hypertension and headache, of hypertension with prostatic hypertrophy, in which the use of an a1-blocker is recommended to control pressure and pollakiuria.

Fortunately, the vast majority of cases of hypertension are represented, as already mentioned, by the mild and uncomplicated form, so the problem of how to set up the therapy is not so crucial and basically identifies with the problem of choosing the drug or drugs more suitable.

The choice of the antihypertensive drug is, in fact, still today substantially empirical.

In fact, we do not have criteria that allow us to make rational therapeutic choices, that is, based on the pathophysiological characteristics of the hypertensive state.

At most, we can rely on some clinical data, which have some relevance to pathophysiology, but which are not strictly pathophysiological.

Initial choice of antihypertensive therapy according to the complications of hypertension

- Left Ventricular Hypertrophy: ACE Inhibitors, Ang II AT1 receptor blockers, calcium channel blockers, central antiadrenergics

- Acute Myocardial Infarction: beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors

- Angina pectoris: beta blockers, calcium channel blockers

- Hypertensive nephropathy and mild renal insufficiency: ACE inhibitors, calcium channel blockers, central antiadrenergics, alpha1 blockers, loop diuretics

- Advanced renal failure: calcium channel blockers, central antiadrenergics, alpha-blockers, loop diuretics

- Heart failure: ACE inhibitors, Ang II AT1 receptor blockers, diuretics

- Claudication: calcium channel blockers, alpha1 blockers, ACE inhibitors, Ang II AT1 receptor blockers

- The first of the criteria that should guide the doctor in choosing the drugs to use is represented by good tolerability.

The latter is good even with the exceptions of the side effects indicated above for the individual categories

It is however frequent that at the beginning of the treatment the patient feels that slight sense of physical, psychological and sexual asthenia, which so often accompanies the very drop in blood pressure in patients accustomed to high tension regimes: it is in fact a transitory phenomenon, that can not exempt the doctor from pursuing his primary objective which is to bring blood pressure back to normal values or as close as possible to the norm.

In the choice of the antihypertensive drug, another criterion is the physiopathological-clinical one:

- Initial choice of antihypertensive therapy according to the clinical-demographic characteristics of the patient

- Dyslipidemia, multimetabolic syndrome: alpha1 blockers, ACE inhibitors

- Hyperuricaemia: losartan

- Hyperkinetic syndrome: beta blockers

- Pregnancy: alfamethyldopa, atenolol

- Diabetics: ACE inhibitors, calcium channel blockers

- Black race: diuretics, calcium channel blockers

The choice is made on the basis of some clinical characteristics of the patient under examination, characteristics that are a reflection of his physiopathological condition.

Faced with a young and tachycardic hypertensive person, who therefore certainly has hyperkinetic circulation and probably a high cardiac output, the choice is easily oriented towards the use of a beta blocker.

On the other hand, when faced with a bradycardic patient and in whom there is a prevalent increase in diastolic pressure, the doctor is authorized to hypothesize that the cardiac output is normal and the peripheral resistance increased, so he will orient his choice towards a drug with vasodilating activity. .

Finally, if the increase in systolic pressure prevails and the differential pressure is high, it is very likely that, in addition to the increase in arteriolar resistance, there is also a lower compliance of the large elastic vessels, therefore it is possible to use active drugs both on the small ones. arterial vessels than on large elastic vessels, i.e. calcium antagonists or ACE inhibitors.

Other criteria for orientation in the choice of antihypertensive drugs could come from laboratory tests.

The finding of hypokalaemia outside of any previous diuretic treatment will lead to control of plasma renin activity.

If this is high (after excluding correctable secondary renovascular hypertension), it will be logical to direct one’s initial preference towards inhibitors of the conversion enzyme and blockers of the AT1 receptor of ANG II; if it is low, it will be more logical to think of hypervolemic hypertension and move towards diuretics, naturally associating spironolactones with thiazides, due to hypokalemia and possible hyperaldosteronism, albeit latent.

The detection of hyperuricemia or hyperglycemia will also make the use of diuretics cautious, taking into account the biochemical side effects of this group of drugs.

Other elements to be taken into account are those deriving from an overall clinical evaluation of the patient, with particular regard to the presence of any associated pathologies and, in the case of severe hypertension, complications of the hypertension itself.

It is only necessary to remember the caution with which beta-blockers must be used in diabetic patients, and the contraindications constituted by the presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma, a.v. block, a left ventricular decompensation.

Beta-blockers are also contraindicated in those hypertensive who have intermittent claudication due to atherosclerosis of the arteries of the limbs: in such cases, drugs with vasodilating action (ACE inhibitors, calcium antagonists, a1-blockers) will obviously become the drugs of first choice.

In hypertensive patients with angina-type coronary artery disease, beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers will be the drugs of choice, at least in the first instance. In the case of a previous heart attack, the use of beta-blockers and ACE inhibitors is imperative, unless there are other contraindications, since various studies have shown their effectiveness in preventing re-infarction and sudden death.

In hypertensive patients with overt renal insufficiency, the use of diuretics is rational, since they are mostly hypervolemic patients; however, the choice of diuretic must be prudent, given that in patients with particularly low creatinine clearance the only effective and well tolerated diuretics are loop diuretics, used at higher doses than usual.

The case series could lengthen, but it is enough here to have cited some examples to remember that in every hypertensive patient, the clinical evaluation must be thorough and complete if the therapeutic approach is to have some rationality or even not be harmful.

Read Also:

Emergency Live Even More…Live: Download The New Free App Of Your Newspaper For IOS And Android

Heart Failure: Causes, Symptoms And Treatment

The Thousand Faces Of Vascular Disease

Blood Pressure: When Is It High And When Is It Normal?

Metabolic Syndrome: Why Not To Underestimate It

Endocrine And Metabolic Emergencies In Emergency Medicine

Drug Therapy For The Treatment Of High Blood Pressure

Assess Your Risk Of Secondary Hypertension: What Conditions Or Diseases Cause High Blood Pressure?

Pregnancy: A Blood Test Could Predict Early Preeclampsia Warning Signs, Study Says

Everything You Need To Know About H. Blood Pressure (Hypertension)

Non-Pharmacological Treatment Of High Blood Pressure

Blood Pressure: When Is It High And When Is It Normal?

Kids With Sleep Apnea Into Teen Years Could Develop High Blood Pressure

High Blood Pressure: What Are The Risks Of Hypertension And When Should Medication Be Used?

Ischaemic Heart Disease: What It Is, How To Prevent It And How To Treat It

Ischaemic Heart Disease: Chronic, Definition, Symptoms, Consequences