What is and how to read the allergy patch test

The patch test is the fundamental examination for the diagnosis of allergic contact dermatitis, a pathological condition of the skin with manifestations similar to other forms of eczema, whether irritative or atopic

The first step to treating these dermatitis in the most correct and effective way is to discover their real origin thanks to the patch test, which differentiates irritative dermatitis from allergic contact dermatitis.

What is the patch test?

The patch test is a so-called in vivo diagnostic test, indicated to identify the cause in cases of:

- suspected contact allergy (CAC);

- skin diseases that may present a secondary allergy;

- certain forms of adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

Jozef Jadassohn (professor of dermatology at the University of Wroclaw, now Wroclaw, Poland) is the father of the patch test

With his discovery in 1895, he recognised the possibility of eczematous reactions occurring in some (sensitised) patients when chemicals were applied to their skin.

Bruno Bloch (Professor at the Universities of Basel and Zurich) continued and extended Jadassohn’s clinical and experimental work.

Today, patch tests or epicutaneous tests are a nationally and internationally standardised method and require specific expertise in reading the results.

They have value in the medico-legal field and for the recognition of occupational diseases’.

How the patch test works

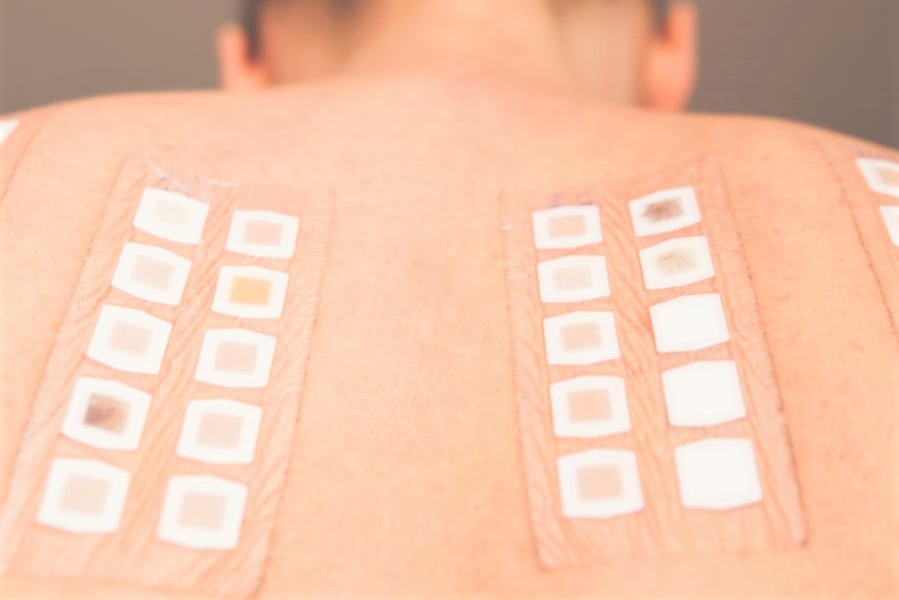

The test is carried out by applying suspected substances (haptens) to the back of the person, appropriately conveyed (in Vaseline, water, ethanol, etc.), prepared at certain concentrations and placed in cells fixed with patches.

The patches are generally kept for 48 hours before removal and readings are taken,’ says the dermatologist.

How to read patch test results

The gold standard for readings is at 48 and 96 hours, but removal can also be done at 72 hours, waiting an hour for the reading.

Some haptens can give particularly delayed responses (acrylates, neomycin, lanolin, nickel…) and so a further reading may be necessary after 7 days.

Once the patches have been removed, the dermatologist assesses the appearance of any erythema, oedema (swelling) and blistering to define positive reactions and establish their gradient, from +, which are doubtful reactions, to +++, positive reactions.

A certain amount of experience is required to discriminate true positive reactions from false positive reactions (e.g. erythematous, pustular, etc.) and from reactions of an irritative nature.

Haptens or suspicious substances examined by patch testing

The most significant haptens (suspect substances) to be tested are established by scientific societies and are then continuously updated.

Currently, it is possible to perform the standard European series established by the European Society of Contact Dermatitis (ESCD).

There are also a number of integrative series that can be used as an in-depth diagnostic test and in the case of precise clinical suspicions.

What the patch test diagnoses: DAC and DIC

The patch test, as already mentioned, is the diagnostic tool for investigating in particular allergic contact dermatitis (ACD), which thanks to this test can be distinguished from irritative contact dermatitis (ICD).

Allergic contact dermatitis

Allergic contact dermatitis (ACD) is a common inflammatory dermatitis in both non-occupational and occupational settings.

It accounts for about 90% of all dermatoses defined as ‘occupational’ (i.e. related to the profession).

This pathology arises from an allergic (immune-mediated) reaction to chemical or biological sensitisers.

In the case of allergic contact dermatitis, the immune response to sensitising agents is delayed or cell-mediated and is determined by previous exposure of the immune system to the allergen.

When the person comes into contact again with the substance to which he or she has become sensitive, the cells, previously sensitised T lymphocytes, become activated, release mediators (cytokines) and recruit inflammatory cells, causing the typical symptoms of allergic contact dermatitis.

Symptoms of allergic contact dermatitis

Generally, the disorder manifests itself as punctiform vesicles with a serous content on the areas ‘in contact’ with the substance responsible, but it tends to spread even further.

The sites most exposed to sensitisers are the hands, face, neck, armpits and feet.

The main symptom is itching, but in severe cases there may be pain and even functional impotence.

It is a debilitating condition, especially when the hands are affected, resulting in rhagades and pain that prevent the performance of manual and domestic tasks.

In acute eczema, vesicles with a serous content may rupture and exudate.

In chronic eczema, lichenification, i.e. thickening of the epidermis, which becomes hard and dry, and fissures prevail.

If the cause is not identified and targeted treatment is not given, allergic contact dermatitis can recur, become chronic and lead to complications (e.g. infectious).

Irritative contact dermatitis (ICD)

Allergic contact dermatitis should be distinguished from forms of purely irritative origin, which can give equally serious pictures of inflammatory skin reactions but which result from direct damage of irritants to the skin barrier.

The reaction in this case is not immune-mediated (which is why patch tests are negative) and is confined to the site of contact.

Irritant contact dermatitis (ICD) is more common and is most common in certain occupations, such as construction, mechanics or ‘wet work’, such as hairdressers, housewives and those working in grocery shops.

Skin allergies to nickel, perfumes and preservatives

Nickel, fragrances and preservatives are the main culprits of skin allergies, and we look at them in detail.

Nickel allergy

Nickel is the main cause of allergic contact dermatitis and metal allergy.

It is a metal often found in everyday objects, clothing accessories, costume jewellery, especially earrings.

This is why it is a very common allergy in women (up to 31% of the female population may be affected).

Allergy to perfumes

Perfumes are the most frequent cause of allergic contact dermatitis from cosmetics.

In the general population, the prevalence is 1.9-3.5%, with an increasing trend of sensitisation even in those suffering from atopic dermatitis.

Perfumes are often found in

- cosmetics (creams, shower gel, shampoo, etc.);

- natural products (e.g. in essential oils);

- detergents and fabric softeners;

- additives and sanitisers.

As fragrances are present everywhere, it is possible to have recurrences of allergic contact dermatitis after using even very different products (detergents, insecticides, plants and even foods).

Allergy to preservatives

Other frequent sensitisers are preservatives, components of cosmetics used to prevent contamination by microorganisms.

Among these, the most frequently used are:

- Euxyl K 400, a mixture of phenoxyethanol (80%) and dibromodicyanobutane (20%), the latter being the one with the highest sensitising power.

- Kathon CG, a mixture of methylisothiazolinone and chloromethylisothiazolinone, mainly contained in cosmetics, detergents and fabric softeners. Recently, there has been a real ‘epidemic’ of allergic reactions, so their use as preservatives in cosmetics is now regulated in Europe, and they are only permitted in low concentrations in rinse-off products and banned for leave-on products such as creams and cleansing milks.

- Formaldehyde, used in industry and considered a ubiquitous allergen. European regulations currently restrict its use to rinse-off products and nail polish (formaldehyde resins). Another important source of sensitisation are preservatives that release formaldehyde (imidazolidinylurea, Quaternium15, diazolidinyl urea, DMDM hydantoin, bronopol). These may be present in cosmetics such as face creams, mascaras, foundations, deodorants, shampoos, hair conditioners, nail hardeners, toothpastes and in topical medicines.

- Parabens, a class of aromatic organic compounds with bactericidal and fungicidal functions. Methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben and butylparaben are the most commonly used preservatives in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, the food industry and various other industrial products. Considering the wide use of parabens in cosmetics (90% of leave-on products and 77% of rinse-off products contain parabens), the frequency of allergic reactions is rare, although they have been highly criminalised in recent years (compared to other preservatives).

Other possible sensitising agents

Other sensitising agents include other metals: cobalt and chromium as well as nickel, but also those used in oral implantology such as palladium or in orthopaedic prostheses.

Sensitisations to hair dyes and acrylates in artificial nails are also increasingly common.

In addition, sensitisation to synthetic fabric dyes, rubber additives, plastics, resins, etc. is also common.

Finally, beware of natural extracts or phytoextracts, which are frequently used in perfumes, cosmetics (lotions, ointments, creams) and topical medicines and can cause sensitisation, although they are generally considered ‘harmless’.

Contraindications to patch testing

Patch testing is not recommended after ultraviolet therapy or recent intense sun exposure.

If patch tests are performed during immunosuppressive treatments (which just cannot be discontinued), the results should be interpreted with caution due to the possibility of false negatives and, if possible, should be repeated after the end of therapy.

Other situations in which patch testing may not be entirely reliable are active phases or flare-ups of allergic contact dermatitis or atopic eczema.

In addition, atopic skin is very easily irritated, so there may be irritative reactions or false positives to patch tests (usually with metals, perfume, formaldehyde and lanolin).

Read Also:

Emergency Live Even More…Live: Download The New Free App Of Your Newspaper For IOS And Android

Adverse Drug Reactions: What They Are And How To Manage Adverse Effects

Symptoms And Remedies Of Allergic Rhinitis

Allergic Conjunctivitis: Causes, Symptoms And Prevention