What is chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (CMML)?

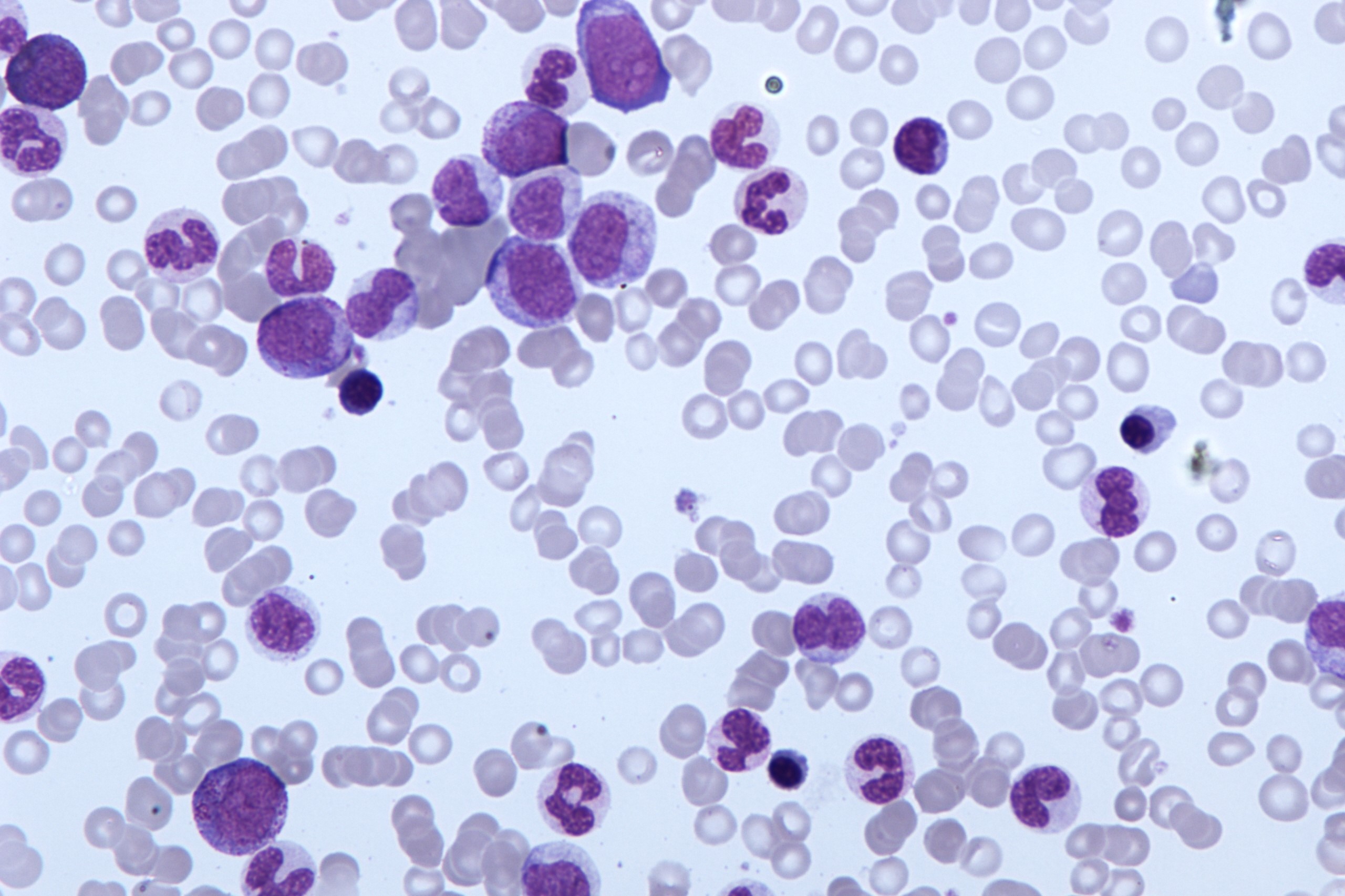

Chronic myelomonocytic leukaemia (CMML) is a rare type of blood cancer. In CMML there are too many monocytes in the blood. Monocytes are a type of white blood cell

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has included CMML in a group of blood cancers called myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic disorders

CMML is a separate condition with different treatment options because people with CMML can have features of both myeloproliferative disorders (MPN) and myelodysplastic disorders (MDS).

Bone marrow and blood cells

The bone marrow is the soft inner part of our bones that produces blood cells.

All blood cells start from the same type of cell called a stem cell. The stem cell produces immature blood cells.

These immature cells go through various stages of development before becoming fully developed blood cells.

The bone marrow produces several types of blood cells, including:

- red blood cells to transport oxygen in the body

- white blood cells to fight infection

- platelets to aid blood clotting

The diagram shows how different cell types develop from a single blood cell.

What are myeloproliferative and myelodysplastic diseases?

A myeloproliferative disease is a condition in which too many blood cells are produced.

A myelodysplastic disorder is where the blood cells produced are abnormal and not fully mature.

In reality, the two disorders often overlap, which is why the WHO has lumped them together here in the same category.

In CMML it is a specific type of white blood cells called monocytes that are abnormal

Monocytes are part of the immune system and help the body fight infections.

Too many of them are produced and are not sufficiently developed to function properly.

It is also more difficult for the bone marrow to produce other blood cells such as:

- red blood cells

- platelets

- other white blood cells

This is because monocytes take up a lot of space in the bone marrow.

What happens in CMML?

White blood cells called monocytes help the body fight infections.

In CMML, the bone marrow produces abnormal monocytes.

They are not fully developed and cannot function normally.

Sometimes there is also an increase in immature cells called blast cells.

These abnormal blood cells remain in the bone marrow or are destroyed before entering the bloodstream.

As CMML develops, the bone marrow fills with abnormal monocytes.

These abnormal blood cells then spill into the bloodstream.

Since the bone marrow is full of abnormal cells, it cannot produce enough of the other types of blood cells.

The low number of normal blood cells in the blood stream eventually causes symptoms.

Risks and causes of CMML

We do not know the cause of most cases of CMML, but there are some risk factors that may increase the risk of developing it.

A risk factor is something that may increase the likelihood of developing a particular condition or disease.

The risk of developing CMML increases with age.

The average age at diagnosis is between 71 and 74.

And it is more common in men than in women.

Sometimes, CMML is caused by radiotherapy or chemotherapy treatment for cancer.

This is called secondary or treatment-related CMML.

Gene changes

Research has shown a number of genetic changes that are important in CMML.

About half of all people who have CMML (about 50%) have a change in a gene called TET2.

The TET2 gene produces a protein that controls how many monocytes stem cells produce.

Up to 30 out of 100 people (up to 30%) have a change in a gene called RAS.

The change causes cells to multiply uncontrollably.

There are other genes in which changes could lead to CMML, these include:

- ASXL1

- SRSF2

Many people with CMML have more than one genetic change.

Signs and symptoms of CMML

CMML usually develops slowly and initially causes no symptoms.

When it starts to cause symptoms, they may include

- tiredness and sometimes breathlessness due to a low red blood cell count (anaemia)

- infections that do not improve

- bleeding (such as nosebleeds) or bruising due to a low platelet count

- belly (abdominal discomfort) from a swollen spleen

- rashes or nodules

- shortness of breath from fluid between the sheets of tissue covering the outside of the lung – this is called pleural effusion

Types of CMML

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has divided CMML into 3 types.

They are called type 0, type 1 and type 2.

The number of abnormal myeloid cells (blasts) in the blood and bone marrow samples tells the doctor the type of CMML.

Doctors describe the number of blast cells as a percentage.

This is the number of blasts per 100 white blood cells.

- CMML type 0 means that you have less than 2% blasts in your blood and less than 5% blasts in your bone marrow.

- CMML type 1 means that you have 2-4% blasts in the blood or 5-9% blasts in the bone marrow. Some people have both.

- CMML type 2 means that you have 5-19% blasts in the blood and 10-19% in the bone marrow.

Having Auer rods in your samples means that you have CMML type 2.

Auer rods are material inside the CMML cells that look like long needles.

They can only be seen under a microscope.

And Auer rods can only be seen inside abnormal cells.

Knowing your CMML type, along with other factors, helps your doctor decide your risk group.

And it can help them decide on the best treatment for you.

Risk groups

Physicians use risk groups to try to predict how well CMML would respond to standard treatment.

There are several risk groups that physicians use for CMML.

In general, doctors use the following to find out the risk group:

- your CMML type, which includes the number of blasts in your blood and bone marrow

- the number of white blood cells

- any genetic changes in the CMML cells

- whether you have a low red blood cell count and need red blood cell transfusions

Change (transformation) to acute myeloid leukaemia

CMML can develop into acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) if the number of blasts in the blood exceeds 20%.

Doctors call this transformation.

Transformation occurs between 15 and 30 out of 100 people with CMML (between 15 and 30%).

This may happen after a few months or after several years.

Read Also

Emergency Live Even More…Live: Download The New Free App Of Your Newspaper For IOS And Android

Leukaemia: Symptoms, Causes And Treatment

Leukaemia: The Types, Symptoms And Most Innovative Treatments

Lymphoma: 10 Alarm Bells Not To Be Underestimated

What Is Acute Lymphocytic Leukemia?

Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma: Symptoms, Diagnosis And Treatment Of A Heterogeneous Group Of Tumours

CAR-T: An Innovative Therapy For Lymphomas

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukaemia: Long-Term Outcomes Described For Childhood ALL Survivors

Colour Changes In The Urine: When To Consult A Doctor

Why Are There Leukocytes In My Urine?

Acute Lymphocytic Leukaemia: What Is It?

Rectal Cancer: The Treatment Pathway

Testicular Cancer And Prevention: The Importance Of Self-Examination

Testicular Cancer: What Are The Alarm Bells?

The Reasons For Prostate Cancer

Bladder Cancer: Symptoms And Risk Factors

Breast Cancer: Everything You Need To Know

Rectosigmoidoscopy And Colonoscopy: What They Are And When They Are Performed

Bone Scintigraphy: How It Is Performed

Fusion Prostate Biopsy: How The Examination Is Performed

CT (Computed Axial Tomography): What It Is Used For

What Is An ECG And When To Do An Electrocardiogram

Positron Emission Tomography (PET): What It Is, How It Works And What It Is Used For

Single Photon Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT): What It Is And When To Perform It

Instrumental Examinations: What Is The Colour Doppler Echocardiogram?

Coronarography, What Is This Examination?

CT, MRI And PET Scans: What Are They For?

MRI, Magnetic Resonance Imaging Of The Heart: What Is It And Why Is It Important?

Urethrocistoscopy: What It Is And How Transurethral Cystoscopy Is Performed

What Is Echocolordoppler Of The Supra-Aortic Trunks (Carotids)?

Surgery: Neuronavigation And Monitoring Of Brain Function

Robotic Surgery: Benefits And Risks

Refractive Surgery: What Is It For, How Is It Performed And What To Do?

Anorectal Manometry: What It Is Used For And How The Test Is Performed