Wounds infection control: Smart bandage gives signals by turning fluorescent

Colour-changing burns dressing will help in the fight against infection and antibiotic resistance

Researchers have developed a new kind of wound dressing that could serve as an early-detection system for infections. Source: MIT Technology Review

WHY IT MATTERS

Wound infections can severely compromise patient health, and caring for infected wounds costs billions of dollars annually.

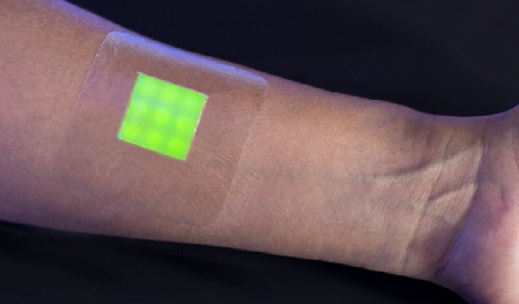

Bacterial infection is a fairly common and potentially dangerous complication of wound healing, but a new “intelligent” dressing that turns fluorescent green to signal the onset of an infection could provide physicians a valuable early-detection system.

Researchers in the United Kingdom recently unveiled a prototype of the color-changing bandage, which contains a gel-like material infused with tiny capsules that release nontoxic fluorescent dye in response to contact with populations of bacteria that commonly cause wound infections.

Led by Toby Jenkins, a professor of biophysical chemistry at the University of Bath, the inventors of the new bandage, which has not yet been tested in humans, say it could be used to alert health-care professionals to an infection early enough to prevent the patient from getting sick. In some cases it may even be able help avoid the need for antibiotics, says Jenkins.

Jenkins’s group is collaborating with clinical researchers from a pediatric burn center at the University of Bristol, and the team envisions that one of the first applications could be burn treatment. Clinicians tend to overprescribe antibiotics for burn wounds, particularly in children, because they are so concerned about infection. That can lead to antibiotic-resistant strains. An infection-detecting bandage could prevent this by reassuring parents and doctors when a wound is in fact not infected. They would also be useful for monitoring surgical wounds as well as those that result from traumatic injury, says Jenkins.

All wounds get colonized by bacteria, often including pathogenic species, but small populations are generally not harmful, and the immune system can clear them. In some cases, though, a population of harmful bacteria grows too big for the immune system to handle, and clinical intervention is needed to clear it. “We believe that this transition normally happens several hours, if not longer, before any clinical symptoms become evident,” says Jenkins. Earlier detection might give doctors time to head off the infection even before such symptoms arise.

Jenkins says the transition is “almost certainly” associated with the formation of a so-called biofilm, a layer of microbes that work together and secrete a slimy substance to defend the colony against the immune system. At a high enough population density, the bacteria film switches on the production of toxins, says Jenkins. The new dressing works because the outer layer of the dye-containing capsules is designed to mimic aspects of a cell membrane. Toxins puncture the capsules like they would cells in the body, releasing the dye, which fluoresces when it is diluted by the surrounding gel.