CPR in pectus excavatum patients: Is it time to say more?

ORIGINAL LETTER ON RESUSCITATION – Early initiation of effective chest compressions is a fundamental aspect of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). According to the current American Heart Association (AHA) and European Resuscitation Council (ERC) CPR Guidelines rescuers should perform high-quality/optimal chest compressions for all victims in cardiac arrest using an adequate compression rate (at least 100 min−1) and a depth of at least 5 cm for adult and of least one-third of the anterior–posterior diameter of the chest or about 4 cm in infants.1, 2 The rescuers should place the heel of one hand in the centre of the victim’s chest (which is the lower half of the victim’s sternum), the heel of the other hand on top of the first hand and interlock the hands fingers, ensuring that pressure is not applied over the victim’s ribs. However, current AHA and ERC CPR Guidelines do not give any advice about chest compression technique in patients with chest wall deformities such as pectus excavatum.

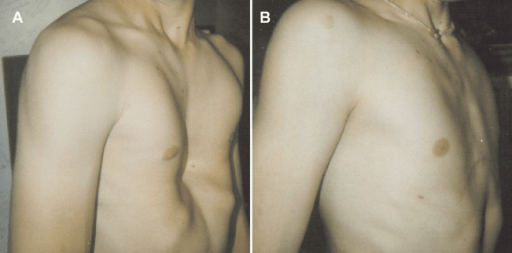

Pectus excavatum (PE) occurs in 1 of every 400 white male births and is a congenital chest wall deformity in which several ribs and the sternum grow abnormally, producing a concave, or caved-in, appearance in the anterior chest wall. The appearance of the defect varies widely, from mild to very severe, in which the posterior displacement of the sternum produces an anterior indentation and deformity of the right ventricle or a rotationally displacement into the left hemithorax. This displacement can cause mechanical compression and obstruction to normal outflow which may impede normal stroke volume. Nuss et al. have developed a miniature-access repair of PE, which requires a metal bar to be temporarily placed within the patient’s chest wall. This bar applies pressure to the underside of the sternum, remodels the affected cartilages, and enlarges the intrathoracic space.

There is only one report about CPR in a patient with a sternal Nuss bar, in which paramedics reported difficulty in performing CPR because of high resistance against compressions, but they had been able to obtain a weak pulse while performing compressions.4 The authors concluded that patients and their families need to understand the potential risks of pectus bars and the inability to perform successful CPR. Mechanical chest compressions might be useful to enhance perfusion during resuscitation from cardiac arrest and to improve survival; however no data are still available in PE patients and there is insufficient evidence to support the routine use of this device in general population.

Current AHA and ERC guidelines do not give any information about CPR technique (proper compression depth and hands position) in PE patients who have not had surgical correction and no cases have been reported in literature.

In a recent retrospective study, CT was used to determine the proper compression landmark and depth of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in PE patients.5 The authors showed that displacement of the heart to the left was significantly greater in PE patients, with mean difference of 11 mm compared with controls, and that the left ventricle was located in all PE patients at the level of lower half of the sternum; they suggested this landmark is appropriate for CPR in PE patients. They defined the external thickness of the chest as the distance between the anterior and posterior skin margin and the internal thickness as the distance between the posterior sternum and anterior vertebrae. The authors showed that the mean external/internal thickness ratio (ET/IT) in PE patients was smaller than in controls, with a mean difference of about 20 mm. When a theoretical compression depth of 5–6 cm was applied to the control patients the estimated residual IT was 3.3–4.3 cm in controls but only 1.0–2.0 cm in the PE patients; thus, application of standard compression depths might increase the risk of myocardial injury or other intrathoracic organ damage in PE patients. The authors concluded that PE patients might need less chest compression depth (i.e. 3–4 cm) than normal subjects.

Until further studies are available, we recommend strong chest compressions, according to the current guidelines, in PE patients with a sternal Nuss bar and, to minimize the risk of myocardial injury, we suggest a reduced chest compression depth (approximately 3–4 cm) at the level of lower half of the sternum in PE patients who have not had corrective surgery.

Vincenzo Russo, Chair of Cardiology, Second University of Naples, Monaldi Hospital, Italy – SIMAID, Naples, Italy

Marco Ranno, Chair of Cardiology, Second University of Naples – Monaldi Hospital, Italy

Gerardo Nigro, InfoEmergency American Heart Association Training Site – SIMAID, Naples, Italy