Medieval medicine: between empiricism and faith

A foray into the practices and beliefs of medicine in medieval Europe

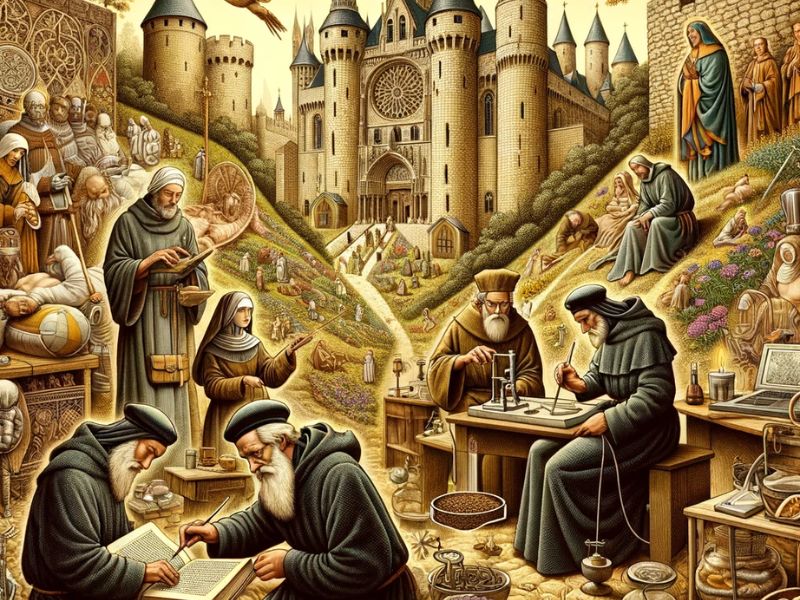

Ancient roots and medieval practices

Medicine in medieval Europe represented a blend of ancient knowledge, diverse cultural influences, and pragmatic innovations. Maintaining the balance of the four humors (yellow bile, phlegm, black bile, and blood), physicians of the time relied on standardized initial examinations to assess patients, considering elements such as residency climate, habitual diet, and even horoscopes. Medical practice was deeply rooted in the Hippocratic tradition, which emphasized the importance of diet, physical exercise, and medication in restoring humoral balance.

Templar healing and folk medicine

Parallel to medical practices based on Greco-Roman tradition, there existed Templar healing practices and folk medicine. Folk medicine, influenced by pagan and folkloric practices, emphasized the use of herbal remedies. This empirical and pragmatic approach focused more on curing diseases than on their etiological understanding. Medicinal herbs, cultivated in monastic gardens, played a crucial role in medical therapy at the time. Figures like Hildegard von Bingen, while educated in classical Greek medicine, also incorporated remedies from folk medicine into their practices.

Medical education and surgery

The medical school of Montpellier, dating back to the 10th century, and the regulation of medical practice by Roger of Sicily in 1140, indicate attempts at standardization and regulation of medicine. Surgical techniques of the time included amputations, cauterizations, cataract removals, tooth extractions, and trepanations. Apothecaries, who sold both medicines and supplies for artists, became centers of medical knowledge.

Medieval diseases and the spiritual approach to healing

The most feared diseases of the Middle Ages included the plague, leprosy, and Saint Anthony’s fire. The 1346 plague devastated Europe without regard to social class. Leprosy, although less contagious than believed, isolated sufferers due to the deformities it caused. Saint Anthony’s fire, caused by ingesting contaminated rye, could lead to gangrenous extremities. These diseases, along with many other less dramatic ones, outlined a landscape of medical challenges often addressed with a spiritual approach, alongside the medical practices of the time.

Medicine in the Middle Ages reflected a complex interweaving of empirical knowledge, spirituality, and early professional regulations. Despite the limitations and superstitions of the time, this period laid the groundwork for future developments in the field of medicine and surgery.

Sources